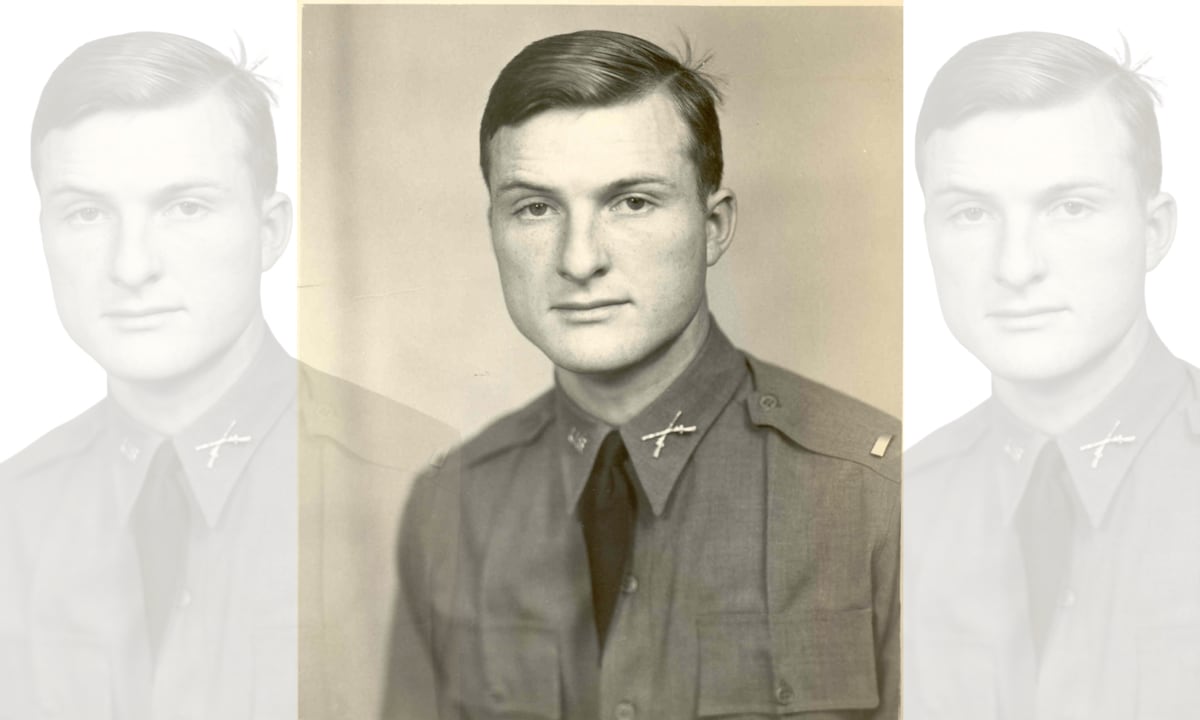

MOH pilot bombed Nazis despite severed limb

It was June 5, 1944 — one day before Allied landings on the coast of German-occupied Normandy — and the American Eighth Air Force was setting out to bomb enemy coastal defenses from the Cherbourg Peninsula to the Pas de Calais.

Among the participating bombers were Consolidated B-24s of the 489th Bombardment Group (Heavy), led by the group’s deputy commander, Lt. Col. Leon R. Vance.

Thanks to the past few months’ onslaught by VIII Fighter Command there was little to no aerial opposition from the Luftwaffe. However, German anti-aircraft guns remained plentiful and continued to take their toll of the American bombers.

On this occasion it was Vance who found himself on the receiving end of that flak — with his B-24 and crew facing heavy odds against making their way home.

Despite graduating from West Point in June of 1939 and assigned to the infantry, Vance managed to wrangle a transfer into aviation. On Sept. 13, 1939, he arrived in Texas for his primary flight training.

Initially a ground officer, Vance decided to switch to flight training and after attending schools at Tulsa, Randolph and Kelly fields, earning his wings in September 1940.

By December 1943 he had qualified on four-engine bombers and had risen rapidly through the ranks to lieutenant colonel and deputy commander of the 489th Bombardment Group (Heavy), then forming at Wendover, Utah. By April 1944 the 489th shipped out to Royal Air Force airfield Halesworth, England, as one of the last groups attached to VIII Bomber Command.

Vance’s first combat mission came a little over a month later, on May 30, 1944, and proved to be a less-than-triumphant debut.

Setting out to strike the German air base at Oldenburg, Vance was leading the group in his first sortie aboard B-24 Sharon D, named after his two-year-old daughter.

As the group crossed the Dutch coast 10 miles south of its briefed checkpoint it ran into a heavy flak barrage. Minutes after removing his helmet because he considered it “uncomfortable,” a navigator was shot dead from a shell splinter. Another plane had to ditch in the North Sea due to a fuel shortage.

In what would only be his second sortie of the war, Vance and the 489th took off on June 5, targeting the fortifications at Wimereux, France.

As the B-24s approached their targets, Vance was standing on the platform behind the pilot and copilot when his plane was bracketed by a concentration of flak. The pilot, Capt. Louis Mazure was killed instantly when a piece of shrapnel struck him on the temple. The copilot, 2nd Lt. Earl Carper, was wounded and Vance’s right foot nearly severed and hanging from the framework.

In spite of the carnage, Vance ordered his men to complete the bomb run before turning for home.

Once the bombs were dropped and the group underway over the North Sea, Vance’s men found three of their engines out of commission, the nose of the plane was shattered, fuel was leaking everywhere and a 500-pound bomb was still hanging up in the bomb bay.

Despite this, Vance and his copilot managed to nurse the plane to the English coast, but when he ordered his crew to take to their parachutes, one told him that their radio operator was too injured to jump.

Vance then ordered the crewmen out, leaving him to try and coax the B-24 into the water.

With his movements limited by what remained of his mangled right foot, Vance worked the ailerons and elevators, using a side window as his sole sighting reference, and managed to ditch the plane on its sole remaining engine.

As Sharon D sank an explosion blew off his injured foot, cutting him clear of it and the plane. Inflating his life jacket and seizing a piece of floating wreckage, Vance spent the next 50 minutes searching for the other crewman, who regrettably never turned up, before an RAF air-sea rescue craft found him.

After two months in hospital, Vance joined other badly injured personnel being evacuated stateside aboard a Douglas C-54 Skymaster.

Tragically, however, on July 26 the transport plane vanished somewhere on the Iceland-to-Newfoundland leg of its transatlantic flight. His body was never recovered.

Vance was recommended to be awarded the Medal of Honor and it was confirmed in January of 1945 — it was the only Medal awarded to a Liberator crewman operating from Britain during World War II. His widow, Georgette Drury Brown, requested to delay the ceremony until the medal could be presented to their daughter.

On Oct. 11, 1946, Maj. Gen. James P. Hodges presented Sharon her father’s Medal of Honor. She was just three-year-old at the time of the ceremony.