Convair NB-36H Nuclear-Powered Bomber

Before the first atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, few in the world understood the potential destructive power that the atom could unleash. While just two cities — Hiroshima and Nagasaki — have experienced the full fury of nuclear weapons, it could be argued the Ukrainian city of Chornobyl and the Japanese towns of Ōkuma and Futaba have respectively faced the wrath of the atom.

Yet, even as two cities were almost completely destroyed, there was a time after World War II when nuclear power was seen as a miracle energy source. For a few years, there was literally nuclear tourism in Las Vegas, where visitors could take a break from the slots and table games to watch an atomic bomb test and see the mushroom cloud rise above the horizon. Clearly, the dangers weren’t appreciated — not even by the brightest minds of the day.

In fact, the scientific magazines of the day suggested a future with mini-nuclear reactors powering everything from trains to cars. Nuclear energy was seen as a clean source of unlimited power.

The U.S. military also quickly embraced nuclear power, and today all of its supercarriers and the entire submarine fleet are nuclear-powered. There were also efforts to create a surface fleet of nuclear-powered cruisers — with the idea being that such warships would have unlimited range and endurance.

However, it wasn’t just the U.S. Navy that sought to be nuclear-powered.

So, Why Not?

The rivalry between the United States Navy, which had been established even as the nation fought for its independence from Great Britain, and the newly formed United States Air Force, was in full swing in the early stages of the Cold War. The services had very differing views on their roles in a full conflict.

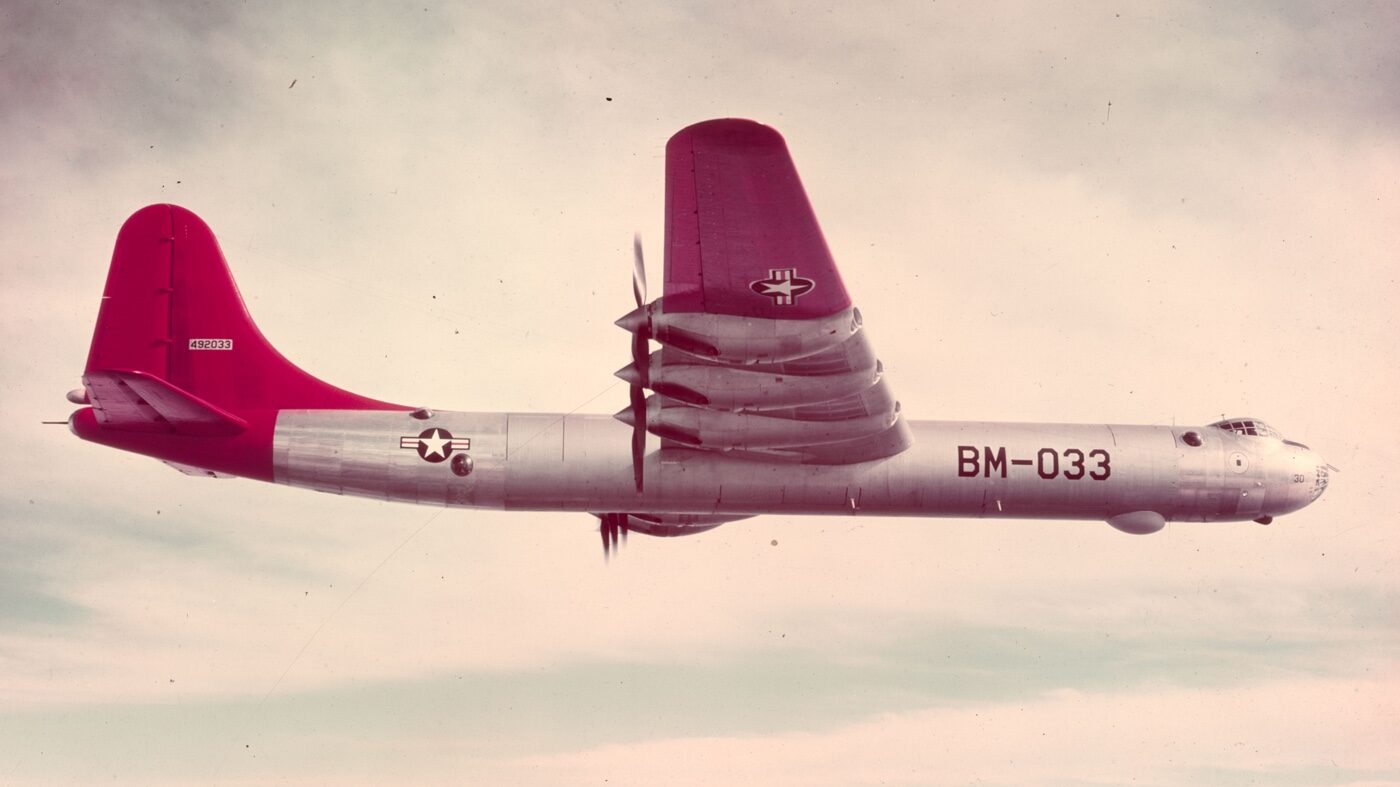

It was, of course, the United States Army Air Force — the forerunner to the U.S. Force — that delivered the atomic bombs to Japan, and efforts were pushed forward to develop even more powerful long-range bombers. That included the Convair B-36 Peacemaker, the largest mass-produced piston-engined aircraft ever built while having the longest wingspan of any combat aircraft.

As designed, the B-36 was capable of intercontinental flight without refueling, but some in the U.S. military considered taking it even further. If nuclear power could offer unlimited range and endurance for a warship, why not a bomber?

One can only assume that those doing the design work didn’t spend hours in the Peacemaker or other bombers of the day.

A Costly Endeavor

In 1946, the Manhattan District, the multi-service program that oversaw the development of the atomic bomb, awarded a contract to the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Company to determine the “feasibility” of employing nuclear energy to power an aircraft.

In hindsight, it is pretty easy to see the problems with the concept. It is one thing for the crews of submarines and supercarriers to spend weeks or longer at sea, yet aircraft lack the creature comforts to support operations for more than a few days at most.

Those issues must have been ignored, if they were considered at all.

The book Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940, edited by Stephen I. Schwartz and produced as part of the Brooking Institute’s study, “The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Cost Study Project,” completed in August 1998, stated: “Between 1946 and 1961, the Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission spent more than $7 billion trying to develop a nuclear-powered aircraft.”

To put that in perspective, the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) — the most expensive warship ever built — cost $13 billion in 2020 dollars. Questions continue to be raised about whether the program is worth the money. By comparison, the nuclear-powered aircraft program would have cost more than $60 billion in 2024 dollars. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), which succeeded the Manhattan District, even determined that to develop a nuclear-powered aircraft would have taken 15 years and cost billions more.

And yet, the program went forward. It may have been an example of one that was too big to fail.

Taking Flight

In May 1946, Fairchild received its first formal study contract, and the project became known as the Nuclear Energy for Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA), and work began at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee. It was soon determined that building a nuclear-powered aircraft was at least feasible and it set out to define the major approaches to the program. The Air Force and AEC partnered and launched the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) Program. This evolved into far more than a simple study.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, around 175 people were at the managerial level, with nearly 8,000 people employed in prime-contract work, and nearly the same number in subcontracts. However, it should be noted that the ANP effort also expanded to explore the possibility of using nuclear power for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), including spacecraft.

In 1951, ANP contracted General Electric (GE) to develop a nuclear-powered propulsion system and to aid in the development, design, and component testing of the necessary reactors, materials, shielding, and most notably the “overall nuclear power plant.”

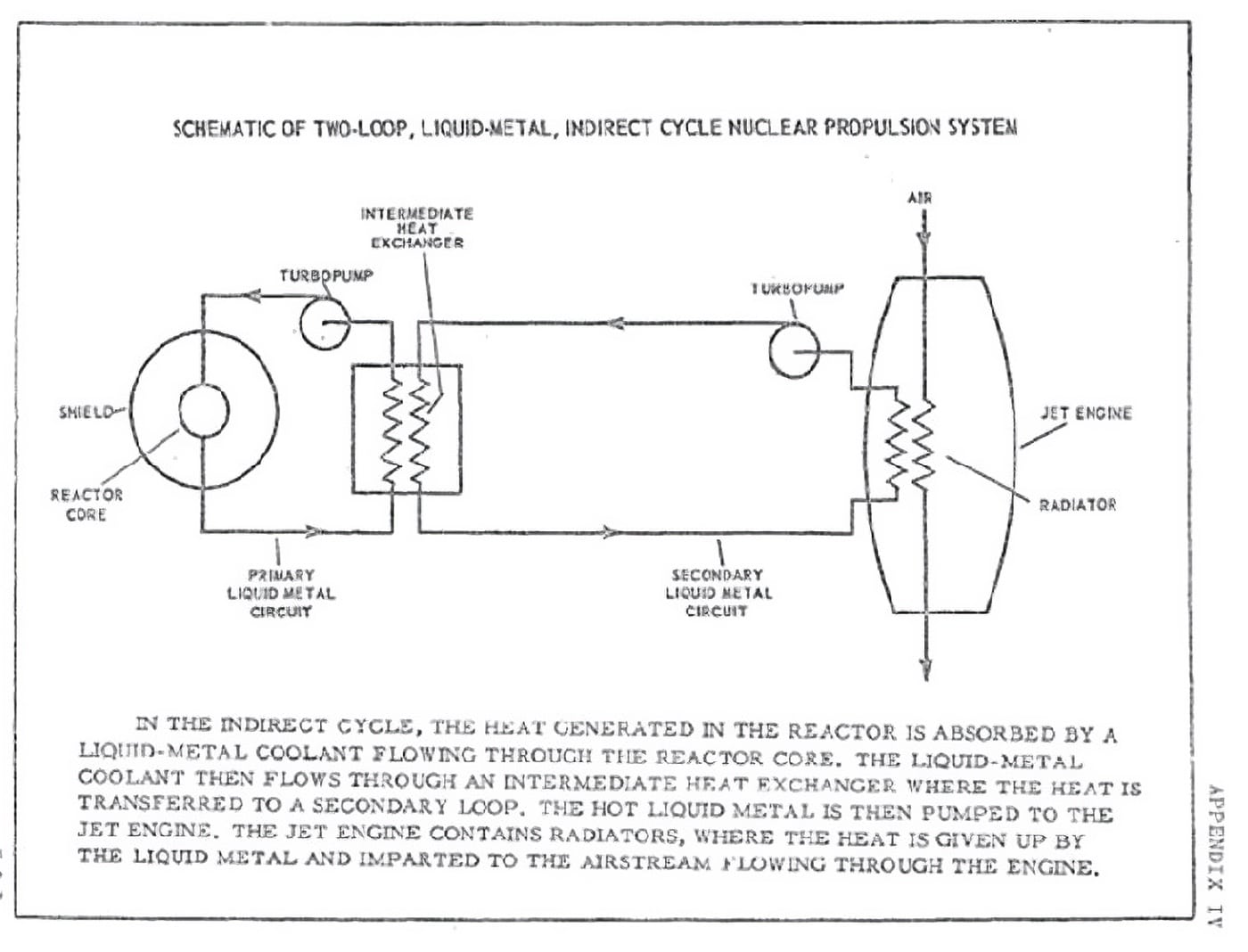

Early into the program, two competing design concepts emerged for a nuclear-powered aircraft — including “Direct-Air-Cycle” and “Indirect.” GE opted for the former, seeing that it offered simplicity, flexibility, adaptability, and ease of handling.

Peacemaker Test Platform

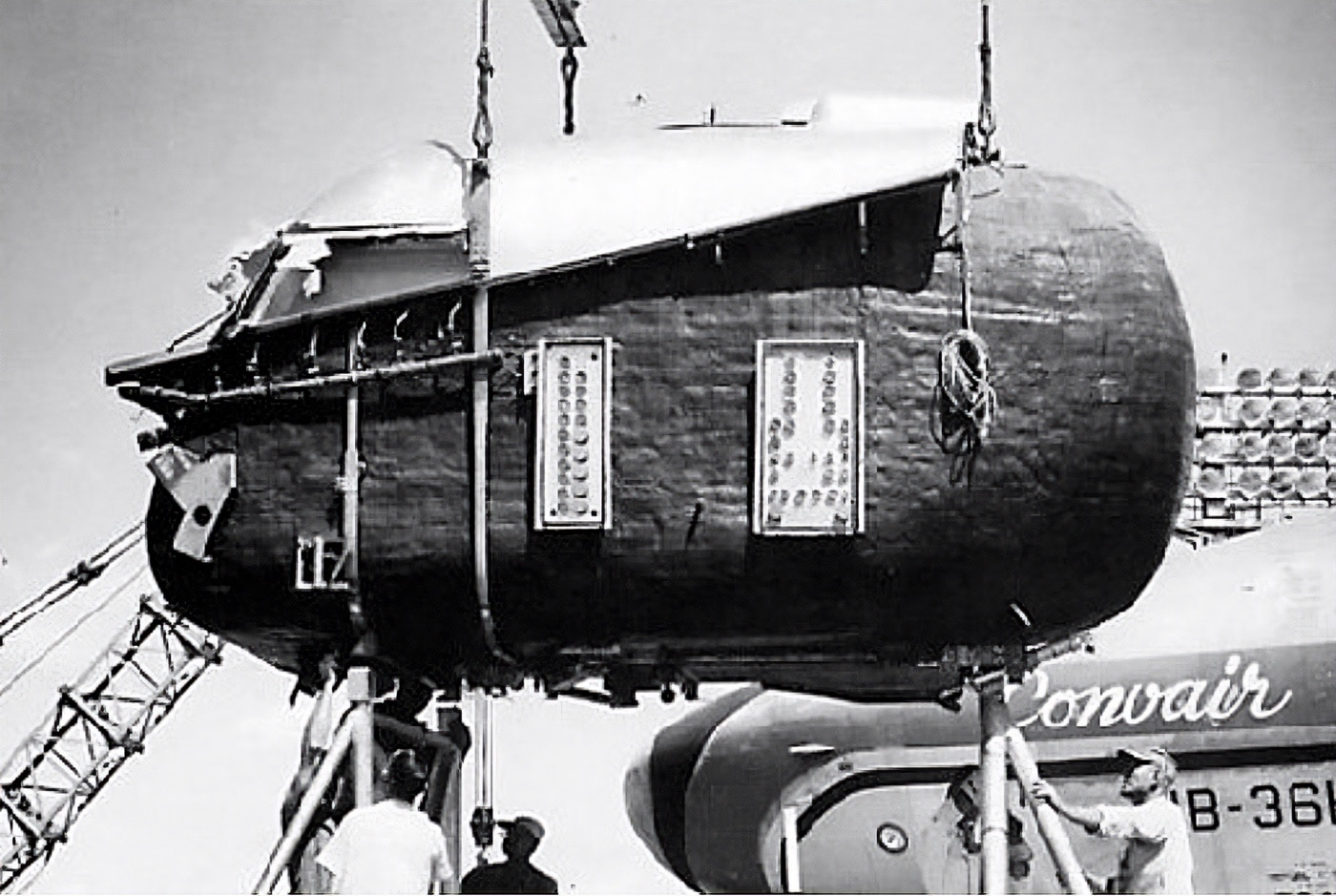

In 1953, as the program moved forward, the Air Force proposed to use the B-36 Peacemaker as the test bed. A bomber that had been heavily damaged in a tornado in 1952 was selected as its airframe was deemed to be a “write-off.” Instead of scrapping it, the B-36 was rebuilt with a completely new nose section that featured a shielded cockpit.

Redesignated the NB-36H, it was fitted with an air-cooled nuclear reactor in the rear bomb bay to determine operation problems. The reactor, developed by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, weighed approximately 35,000 pounds. Despite its mass, it was still designed to be easily loaded and unloaded and kept on the ground between test flights.

Moreover, although it carried the reactor, the bomber was still powered by its six gas-powered piston engines.

The aircraft was fitted with that new nose section that housed a 12-ton lead- and rubber-shielded crew compartment, and 10-12 inch thick leaded glass windows. According to the Brookings Institute study, “Water pockets in the fuselage and behind the crew compartment also absorbed radiation (due to weight constraints, nothing was done to shield the considerable emissions from the top, bottom or sides of the reactor).”

The first flight of the experimental aircraft was conducted on July 20, 1955, from Carswell Air Force Base (AFB), Fort Worth, Texas. Between July 1955 and March 1957, NB-36H conducted 47 flights, totaling 215 flight hours, over Texas and New Mexico with the reactor position in its aft bomb bay. A total of 89 of the flight hours were flown with the reactor in the aircraft. At no point in the testing were the aircraft’s engines ever powered by the reactor.

The crew consisted of a pilot, a copilot, a flight engineer and a pair of nuclear engineers. It should be noted too that the few creature comforts of the aircraft, including its bunks and lavatory, weren’t accessible during flights.

During each of the flights, escorts also trailed the plane — and that reportedly included U.S. Marines who would be ready to respond should there have been an accident.

Success or Failure?

Following the test flights, an Air Force official is reported to have stated, “Our progress has been such that we can confidently expect an airworthy nuclear powerplant to become available in about the length of time required to build a prototype airplane.”

The official added that the prototype “will not necessarily be any larger than the current B-52 … The 4- or 5-man crews of such an aircraft will operate in a quiet and almost vibrationless cabin.”

Based on those words alone, the program could be seen as a success. The Air Force had even envisioned a follow-up project that would power the B-36 with a nuclear reactor. However, that X-6 was never built, and the project was canceled a few years later.

Just as some saw the potential, critics voiced their concerns.

Even before the first flight, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson expressed skepticism about a nuclear-powered aircraft and stated that “experimental ‘proof-of-principal’ flights were worthless unless they were performed by a prototype for an actual weapon system.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower told lawmakers there was no urgency to be placed upon the ANP program. He did authorize $150 million annually for the program to explore the development of a solid-fuel reactor for an Indirect-Cycle engine in development by Pratt & Whitney, while GE continued to receive funding for its Direct-Cycle engine.

After President John F. Kennedy took office in January 1961, he directed a review of all military projects, and GE, P&W and most notably Convair were notified that their respective programs related to the ANP were terminated. The program came to an end not with an atomic-sized bang, but with more of a whimper.

The sole NB-36H was decommissioned, its nuclear reactor removed and the aircraft scrapped. All radioactive elements were buried.

With decades of hindsight, it is easy to see that the program was doomed to failure. The crash of an atomic-powered bomber over the United States could have been catastrophic. Likewise, by the 1960s, the U.S. had developed missiles that lessened the need for a bomber that could fly around the world without refueling.

Other Nuclear Aircraft Programs

It is also worth noting that while the NB-36H was the only U.S. aircraft to be employed in such a nuclear test, the U.S. Navy also launched its own study that considered modifying the British Saunders-Roe Limited Princess seaplane or similarly-sized aircraft into a nuclear-powered flying boat.

The all-metal Princess had taken its maiden flight in 1952, but it seemed to be a solution to a problem that didn’t exist.

As the largest flying boat ever built, it was equipped with six turboprop engines, could carry 100 passengers, and even included first-class cabins. Yet, it was soon determined to be too costly to operate. A single Princess seaplane had been completed and two others were being built when the program came to a halt.

Still, the British Air Ministry had considered options on how it would be used for deploying upwards of 200 troops to distances as great as 3,500 miles. In the late 1950s, the U.S. Navy also explored purchasing the three aircraft to determine if it was possible to convert them to nuclear power. That effort never gained any serious momentum, and nothing came of the sea service’s proposal.

Around the same time as the APN was conducting its study, the Soviet Union began a program to see its Tupolev Tu-95 (NATO reporting name Bear) swept-wing bomber to be powered by a nuclear reactor. Codenamed Lastochka (Swallow), Soviet officials quickly came to see the impractically due to the radiation hazard to the crew and abandoned the project.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!