Consolidated B-24 Liberator: Relentless American Bomber

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress remains arguably the most famous American bomber of the Second World War, and for good reason. It was the workhorse of the U.S. Army Air Force’s daylight bombing campaign against Nazi Germany, and that role solidified its place in history. Yet, even some aviation buffs may be surprised to know that the Flying Fortress wasn’t the most produced U.S. bomber, as that distinction goes to the Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

More than 18,400 were built, surpassing all other bombers in wartime production.

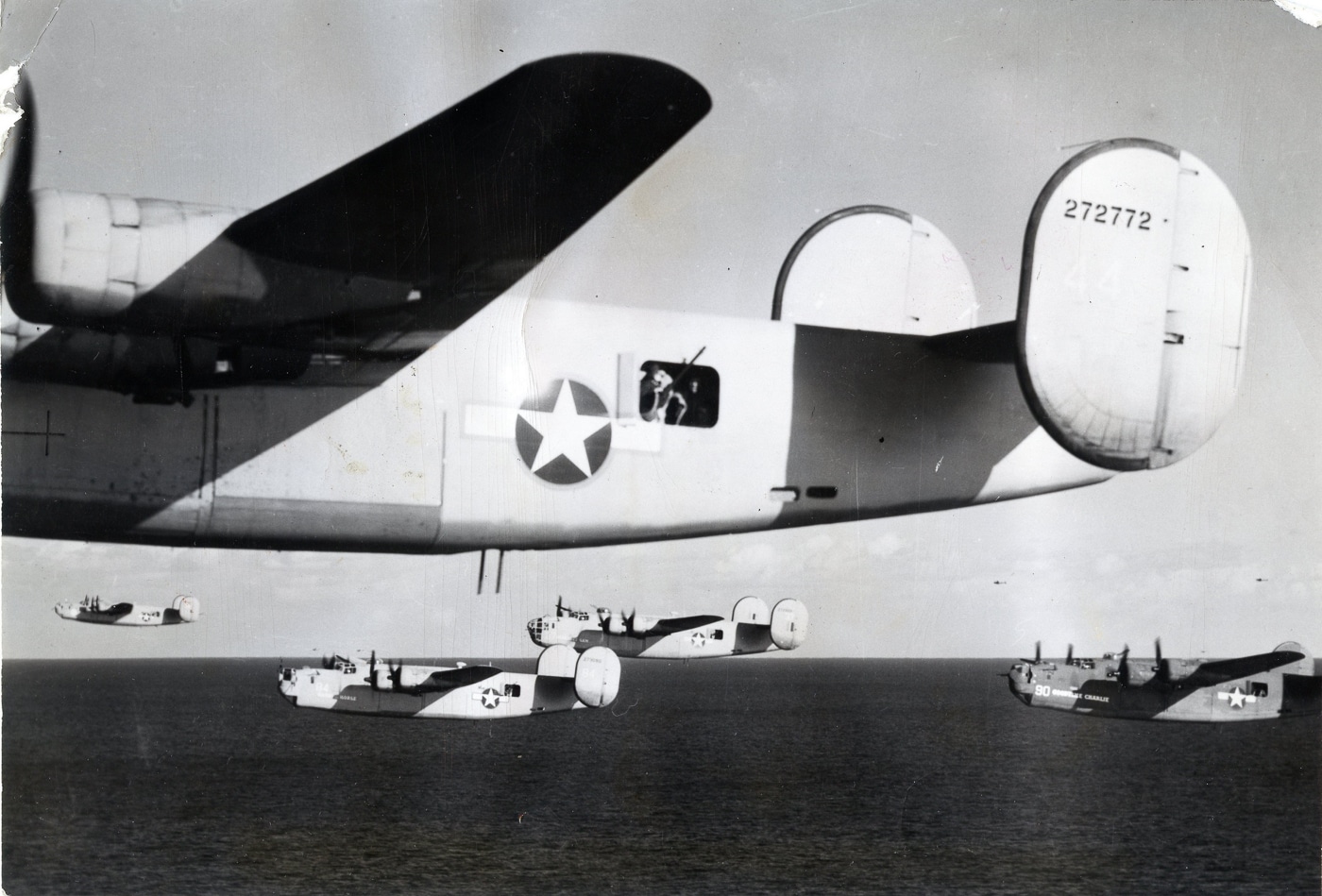

The Consolidated B-24 not only has the distinction of being the most produced American aircraft in history, but it was also built in more versions with more purposes than any other aircraft during the war. It went on to serve on every front during World War II, and with every Allied nation. In terms of industrial effort, the production of the B-24 also transcended anything seen previously.

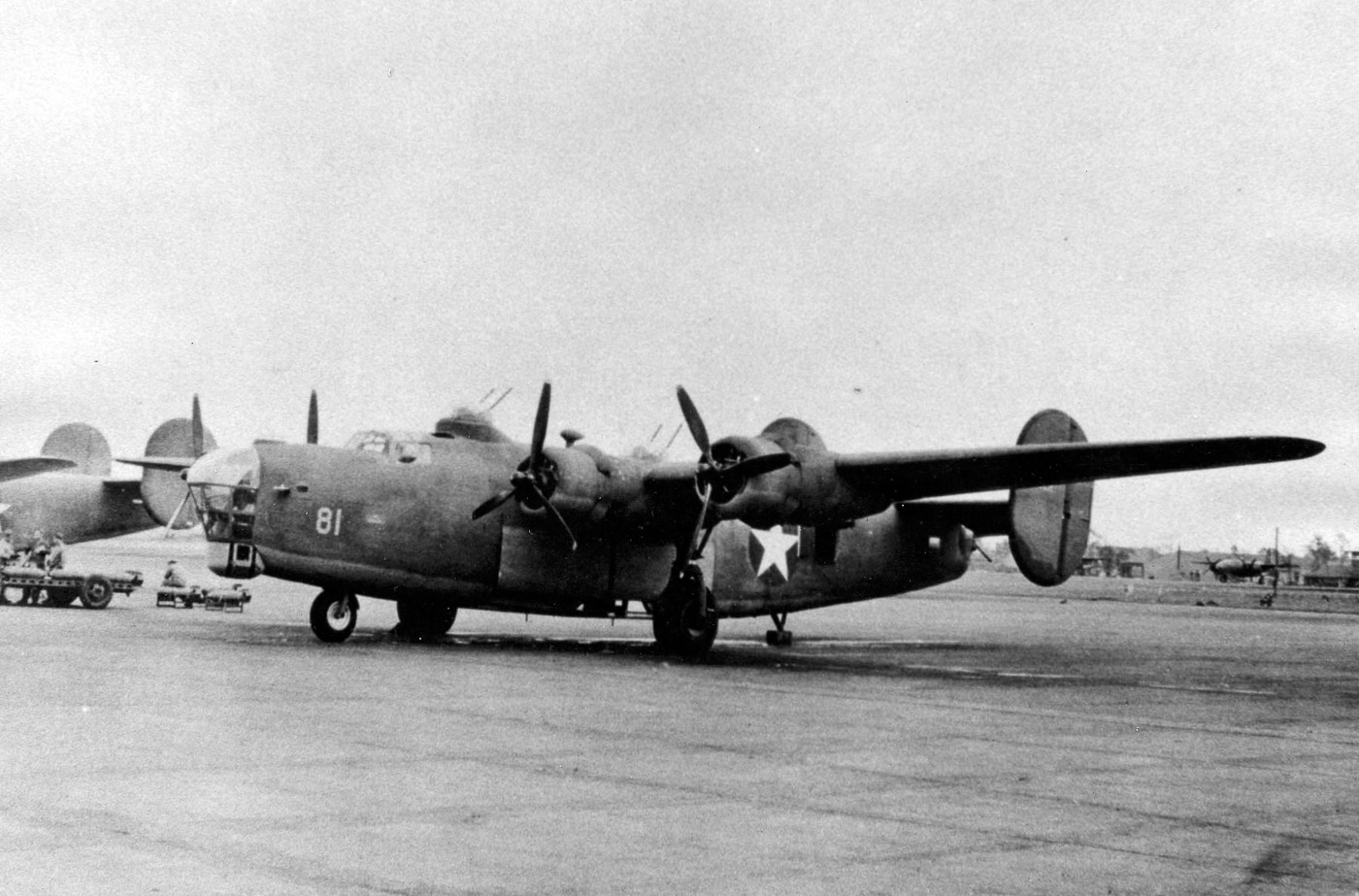

By all accounts, it should have been a monumental leap forward in aircraft design, yet it was not.

Conceived five years after the B-17, the B-24 Liberator arguably didn’t improve on the former bomber’s capabilities in several key areas. In terms of engine performance and general stability, it was inferior. It was described as being a “handful” for the average pilot to handle, while it was also the most complicated and expensive combat aircraft when it was introduced.

The design was unique, and the B-24 featured a layout that was largely dedicated to its Davis wing, which was placed above the tail bomb bays. The Liberator was efficient in cruising flight, which, combined with its excellent fuel capacity, gave it more extended range than any land-based aircraft of its day.

Still, the fact remains that the B-24 is often compared unfavorably with the Flying Fortress, and it hasn’t garnered the glory even as it proved invaluable in its numerous roles from heavy bomber to maritime patrol aircraft. At best, the B-24 wasn’t fully developed when the war broke out and was obsolete by the time it ended, but it served in multiple roles when and where it was needed most.

Development of the B-24

When the United States entered the Second World War following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. Army Air Forces had a mix of bombers in service, including the Marin B-10, the Douglas B-18 Bolo, and notably fewer than 200 B-17s. Production of the Flying Fortress ramped up, but the U.S. War Department was also moving forward with another bomber, the B-24 Liberator.

Interestingly, it was the result of an aircraft maker not opting to build the B-17 when offered the chance.

In late 1938, with the clouds of war on the horizon, the U.S. Army Air Corps had reached out to Consolidated Aircraft to produce the B-17 under license. The company’s founder, Reuben Fleet, and design engineer I. M. “Mac” Laddon, were even given a tour of Boeing’s factory in Seattle, Washington. However, then in January 1939, Fleet presented a counteroffer. Consolidated would produce an aircraft that could strike further, drop more munitions, and survive more punishment than the B-17.

The USAAC liked what it heard, so much so that the company was issued Type Specification C-212, which meant that no other company stood a chance to produce an alternative aircraft. Following a period of frenetic work, Consolidated Aircraft introduced its Model 32, with the Army soon calling for a prototype to be built as the XB-24, which could be flown by the end of 1941.

The most notable aspect of the Liberator’s design was its “fluid foil” wing patented by David R. Davis. It has been suggested that without that unique wing, the B-24 couldn’t have gotten off the ground, literally. Many of the aircraft’s virtues, as well as its faults, could be traced directly to the Davis Wing. It gave the B-24 the load-carrying capacity that exceeded other bombers of its size, and helped make the bomber faster and with a longer range. Yet, it also made the Liberator less maneuverable.

It also resulted in an iconic-looking aircraft, but not one that has been noted for its beauty. It was jokingly called a “Flying Boxcar” while some even suggested it was “the packing box the B-17 came in.”

Despite an external appearance that suggested a roomy interior, it was often cramped, and at altitude, it was also cold as it didn’t feature a pressurized cabin. Even in the Pacific, bomber crews faced bone-chilling temperatures during the long haul missions and bundled up in leather and sheepskin jackets and trousers.

One interesting fact about the aircraft is that while Consolidated was initially approached to build the B-17, during the war, Liberators were produced not only by Consolidated, but also by Douglas, Ford, and North American. Fleet’s pitch should be seen as one for the record books.

In Service with the Mighty Eighth

Although the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was the mainstay and workhorse of the famed Eighth Air Force in Europe, the B-24 Liberator proved to be a crucial part of its bombing operations.

General Ira Eaker, who headed up the U.S. Army Air Forces Bomber Command, championed the use of daylight precision bombing, even as the British Royal Air Force favored night bombing. Eaker argued that the bombers, with their advanced technology, would effectively target specific military and industrial sites during daylight hours, minimizing civilian casualties. Moreover, he initially supported the idea that large bombers like the B-24 could fight their way to a target without help from escorts.

The first bomber missions that hit German-occupied Europe carried out the raids with little or no fighter support. The RAF had already seen that its Lancaster and Halifax bombers were well-armed, but fighters were necessary. Moreover, the RAF supported nighttime bombing.

The Liberator’s baptism of fire came on October 9, 1942, when the 93rd Bomb Group — known as “Ted’s Traveling Circus” and so named for command Colonel Edward “Ted” Timberlake, Jr. — carried out an assault on the French city of Lille. A total of 24 B-24Ds flew with 84 B-17s to the targets. Timberlake was notably at the controls of “Teggie Ann,” B-24D-5-CO Liberator 41-23754.

During the flight, Sgt. Arthur Crandall, a gunner of the 93rd BG, shot down a German Fw 190 from the “Ball of Fiare,” Liberator (41-23667), piloted by Captain Joseph Tate. It was the first aerial victory for a B-24 Liberator serving in the Eighth Air Force in Europe. More importantly, the mission was seen as a significant step in the American air war effort in Europe and demonstrated the capabilities of the B-17s and B-24s. The sortie was also a learning experience, with four aircraft, including three B-17s and one B-24, shot down.

The “Flying Eight Balls” arrived in England in November 1942, and soon after was sortied in its first mission, which was to create a diversion for an attack carried out elsewhere by the B-17. However, the unit soon got in on the action, and by war’s end took part in 343 missions in which it dropped more tons of bombs (18,980 in total) than any other Liberator group save the 93rd. The group claimed 330 Luftwaffe fighters destroyed, but also lost 192 B-24s in the course of the war.

The 93rd BG, the 44th “Eight Balls”, and the 389th “Sky Scorpions” infamously carried out one of the most daring bombing missions of the war in Europe. The heavy bomber groups conducted a dangerous, daytime, low-level raid on the German-held oil refineries in Ploesti, Romania. Around 179 Liberators were chosen as the B-24 could carry a greater bomb load than the B-17, while flying faster and with a greater range. The aircraft formed the “Tidal Wave” — the name for the operation — which saw the aircraft take off not from England, but from Benghazi in Libya.

One of the bombers crashed on take-off in the dust-strewn desert, and another, which happened to be the original lead aircraft, was forced to jettison its bombs early after being attacked by a German Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf 109. In addition, no fewer than 10 B-24s had to abort and return to base due to their engines becoming fouled by the North African sand.

Yet, despite the hardships and even navigation errors that led to some confusion on the approach to the target, the bombers reached Ploesti. However, over the target, some refineries were attacked by too many Liberators and others by too few. It was a costly mission, with 53 B-24s destroyed, another 55 damaged, with 310 aircrews killed or missing, along with 190 aircrews that were captured or interned. Operation Tidal Wave was initially deemed a success, but it quickly became apparent that the damage was less than expected. It further cost the allies aircraft that couldn’t be quickly replaced.

The B-24 Liberator continued to carry out missions in the European and Mediterranean Theaters of Operations (ETO/MTO). The latter was largely carried out by the 15th Air Force, which was created on November 1, 1945. Along with the 8th Air Force, the bombers were used to strike German positions.

By May 1945, the number of B-24 Liberators had fallen from its peak of more than 2,000 to around 1,500. Attrition had been slowly taking its toll, while the aircraft were replaced by the Flying Fortress in Europe.

The RAF’s LB-30 in Europe

Of the 18,431 Liberator aircraft to roll off the assembly line, 2,340 were provided to the UK’s Royal Air Force. Interest in the plane from both the French and British armed forces dated back to its original development, and while the U.S. Army Air Corps had initially just ordered 36, the French Air Force placed an order for 120, while the Royal Air Force sought to obtain 164.

As late as 1940, just before Germany launched its Blitzkrieg campaign, Paris was still optimistic and increased its orders to 175, under the designation LB-30MF (Mission Francais). That contract was taken over when France was quickly defeated, and the UK found itself fighting alone against Nazi Germany.

However, it wasn’t until August 1941, after which the British had been fighting the Germans for nearly two years, that it began to receive the bombers. The aircraft was designated as the Liberator LB-30.

Although it was similar in the B-24C variants, it was built entirely to British specifications and British equipment. The name “Liberator” was also given to the aircraft by the RAF, which was fitting as London hoped to liberate Europe from the Nazis.

As the RAF was already operating its own four-engine bombers, the Liberators in British service filled a variety of roles. The initial batch of nine aircraft, which lacked armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, was deemed unsuitable for combat, and those were subsequently rebuilt as transports. Another 20 were found to be unfit for combat operations and were rebuilt for other roles, which included anti-submarine patrols. Other Liberators were rebuilt as transports, and one, nicknamed the “Commando,” was even used as the personal transport for Prime Minister Winston Churchill during the war.

It is beyond the scope of a single article on the B-24 to go into the plethora of modifications made to the RAF’s LB-30s, but suffice it to say that these were numerous. What is noteworthy is that Liberator B.Mk IIIs were the only ones to serve in a bomber role, and that was only in the Far East.

Liberating the Pacific

The B-24’s operations in Europe have gotten significant attention. Still, a Liberator was also among the first American aircraft lost during World War II, as a B-24A was caught on the ground at Hickam Field, Hawaii, during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The aircraft aided in the liberation of occupied territory in the Pacific and Far Eastern theaters of operation. The USAAF’s 7th and 19th Bomb Groups began operating repossessed LB-30s in the Southwest Pacific in February 1942, just months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The aircraft often flew with B-17s and hunted Japanese convoys, albeit with limited success.

The 11th Air Force in Alaska also employed LB-30s and B-24Ds against the Japanese forces during the campaign in the Aleutians, the only U.S. territory in North America to be invaded. The newly raised 21st and 404 Bomb Squadrons were able to advance from the Aleutian chain to Adak in the fall of 1942, which then put the bombers in range of Japanese targets.

Around the same time, the 10th Air Force India Air Task Force (IATF) Liberators made their first raids on Japanese targets in China, and soon after joined the 5th and 7th Air Forces in the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO). On the night of December 22/23, 1942, the 7th Air Force mounted an attack with 26 B-24s against the occupied Wake Island, staging the attack via Midway from Hawaii. It occurred just a year after the island had fallen to the Japanese.

As the B-17 was phased out of operations in the PTO in 1943, with deliveries of the bomber to Europe, the B-24’s role increased. By the end of the year, the 5th, 7th, 10th, 11th, 13th, and 14th Air Forces were all flying combat missions with the Consolidated bomber.

As encounters with Japanese fighters increased, the bomber was modified accordingly. That led to the introduction of the B-24D model, which was outfitted with turrets being installed in the noses to discourage the attacks. Other developments included the installation of radar to improve bomber accuracy.

The B-24J, the most numerous Liberator variant, entered production in 1944, with most finding their way to the PTO. That was followed by the B-24L and B-24M models. The Liberators took part in bombing raids on the Japanese-occupied Rabaul, an island in New Britain east of New Guinea. It was heavily bombed to avoid a costly invasion, and round-the-clock attacks ensured the island was taken off the board and out of the fight.

The 7th Air Force carried out other B-24 raids from the U.S.-controlled island of Saipan on Iwo Jima. In December 1944, as the U.S. forces were liberating the Philippines, the B-24 Liberators carried out bombing runs on the former American stronghold at Clark Field.

In the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater, B-24s carried out raids against Japanese supply routes into Burma that slowed Tokyo’s desperate offensive to turn the tide of war. At the same time, other bombers dropped mines in occupied harbors and sea lines to disrupt Japanese sea traffic.

And although the raid on Ploesti has been chronicled in great detail, B-24s also bombed former Dutch oilfields and refineries in Balikpapen, Borneo, which supplied the Japanese war effort with 35% of its petroleum, including critical aviation fuel. Throughout the war, Balikpapen came under attack from the 5th and 13th Air Forces on multiple occasions, where more than 300 bombers dropped 433 tons of bombs. It came at a cost of 22 B-24s, yet, Japan’s oil production was significantly curtailed.

The U.S. Navy’s Liberator — The PB4Y

Losses of Allied shipping in the Atlantic to German submarines hunting in the notorious “wolf packs” highlighted a need for long-range patrol aircraft for the United States Navy. The British Coastal Command had already demonstrated the suitability of the Liberator, and the U.S. Navy subsequently adopted the aircraft, which was designated the PB47.

The Liberator, with its long range, was well-suited to the role. Instead of operating as a bomber, it was equipped with surface radar and depth charges. After only a short period of service, the PB47 Liberators helped reduce the shipping losses to German U-boats. The aircraft first operated out of Iceland, and then saw use in the Pacific, carrying out both bombing and patrol duties, bringing havoc to Japanese installations and naval vessels alike.

In the final years of the Second World War, the aircraft was “navalized,” featuring an extended fuselage to accommodate a flight engineer’s station, while the most noticeable change was a tall single vertical stabilizer replacing the B-24’s twin tail configuration. The change was still significant enough that the PB4Y-2 was dubbed the “Privateer.”

The PB4Y-2 saw service in the Korean War, and afterwards, many of the aircraft were converted for weather reconnaissance, with others retrofitted to serve as aerial firefighting planes.

The Privateer is noteworthy for being operated well after World War II by the French military in the Far East and in North Africa. In addition, an unknown number were provided to the National Chinese, which operated the aircraft as patrol planes from Taiwan during the 1960s. One of those aircraft was later suspected of having been shot down by the Burmese Air Force in 1961 after dropping supplies to anti-Communist Kuomintang guerrilla forces operating in the Shan State region.

Honduras acquired at least three of the retired aircraft, which were used as transports, with the aircraft finally retired in the late 1950s.

A Baker’s Dozen Survived

Although more Consolidated B-24 Liberators were built than any other bomber in history, just 13 survive, and only one is airworthy. The number could have been smaller, but 39 that were abandoned after World War II were refurbished and saw service with the Indian Air Force. Those aircraft remained in operation until 1968, and six were preserved.

Of the surviving B-24s, nine were made by Consolidated, with four produced in Fort Worth, and five more in San Diego. The remainder was made by Ford at its Willow Run facility in Michigan. No North American or Douglas models survive, however.

The only airworthy B-24 (Serial Number AM927) is one that was ordered by France and then taken over by the RAF. It is in the collection of the Commemorative Air Force and was converted to the B-24A standard, resembling the type of aircraft operated by the USAAF during WWII.

Military aviation buffs should know that multiple museums now have a B-24 on display and that includes the Hill Aerospace Museum in Roy Utah; the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio; the Castle Air Museum in Atwater, California; the Collings Foundation in Stow, Massachusetts; the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona; the Fantasy of Flight Museum at Polk City, Florida; and the Barksdale Global Power Museum in Bossier City, Louisiana. It was announced in June that the latter B-24 will be transferred from the Barksdale Museum to the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force in Pooler, Georgia.

B-24s that saw service with the RAF are in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Canada; the Royal Air Force Museum in London; the Imperial War Museum Duxford, England; and the Indian Air Force Museum in Delhi, India.

A B-24 is under restoration for display in Australia, while another RAF B-24 is being restored to airworthiness by Project Warbird in South Carolina.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!