Are You Using the Wrong Rifle Scope?

Elk sifted through the logging slash as a tide, its tentacles snaking up toward tall timber. Alas, the bull was mostly hidden in the belly of a draw on the herd’s far fringe. I could only climb to keep abreast.

Then: a lane! I flopped prone on a rise, sling taut. The crosswire settled high on the bull’s shoulder. He dropped to the blast of the .358 Norma.

My scope was a 3-9X Leupold. Though this elk was nearly 300 yards off, I’d left it on 3X, my “carry” setting. I seldom find more power useful on game, and actually prefer smaller scopes.

The longest poke I’ve taken on a hunt was with a scope at 14X. There was no way to pare the yardage. Slinged up prone with a rifle I’d used at distance, I was blessed with still air, perfect light, plenty of time. The bullet landed within a hand’s breadth of my aim, killing the elk. But that was a most unusual event. Of the last six deer I’ve shot, two fell at about 200 yards, the others at less than 100. Five of my last six elk died inside 150. A fixed-power 3X scope suits me.

[Don’t miss the author’s article on how to hunt elk.]

Rifle-scope magnification has increased since 1901, when the J. Stevens Tool Company fielded a 16-inch 5X. Winchester’s A-5 followed, becoming the Lyman 5-A in 1929. Meanwhile in Germany, Zeiss developed a “prism” sight (1904), then bought stock in optics-maker Hensoldt. A 1926 Zeiss catalog listed a Zeilvier 4x at $45, a variable model at $66. In 1930, for the frugal, 24-year-old Texan Bill Weaver designed and hand-built his 3X Model 330. It sold for $19 with a wire-like “grasshopper” mount. In Germany, Zeiss soon found a magnesium fluoride lens coating cut reflection and refraction that could steal up to 4 percent of incident light.

Multi-coatings now further brighten images. But the diameter of the bundle of light sent to your eye (the exit pupil, or EP) is still slave to magnification. To derive EP, divide the scope’s magnification into its objective lens diameter in millimeters. A 3-9×42 scope has an EP of 4.7mm at 9X. Its EP of 14mm at 3X power is more than your eye tap, because a healthy human eye dilates only to 7mm in total darkness, about 6mm in dim shooting light.

A Trifecta

Magnification is one leg of an “optical triangle.” The other two: Eye relief (ER) and field of view (FOV). Increase one at the expense of the others. ER, the distance between your eye and the rear (ocular) glass, must be great enough to keep the scope from bruising your brow in recoil.

Most scopes for receiver mounting on hunting rifles have 3 to 4 inches of ER. Generous latitude in ER is good because it lets you see most or all of the FOV if your eye isn’t exactly the specified distance from the lens. ER is more critical in high-power scopes and usually shrinks a bit as you dial up magnification. ER for my 3-9×40 Leupold is 4.17 inches at 3X and 3.66 inches at 9X.

Top-ejecting lever rifles, Scout rifles and some take-down models beg intermediate-eye-relief (IER) scopes that mount ahead of the receiver. Handgunners require long ERs, as the scope is at arm’s length. A long- or extended-eye-relief (LER, EER) scope has a very small FOV.

[For additional information, watch our video What Is Eye Relief?]

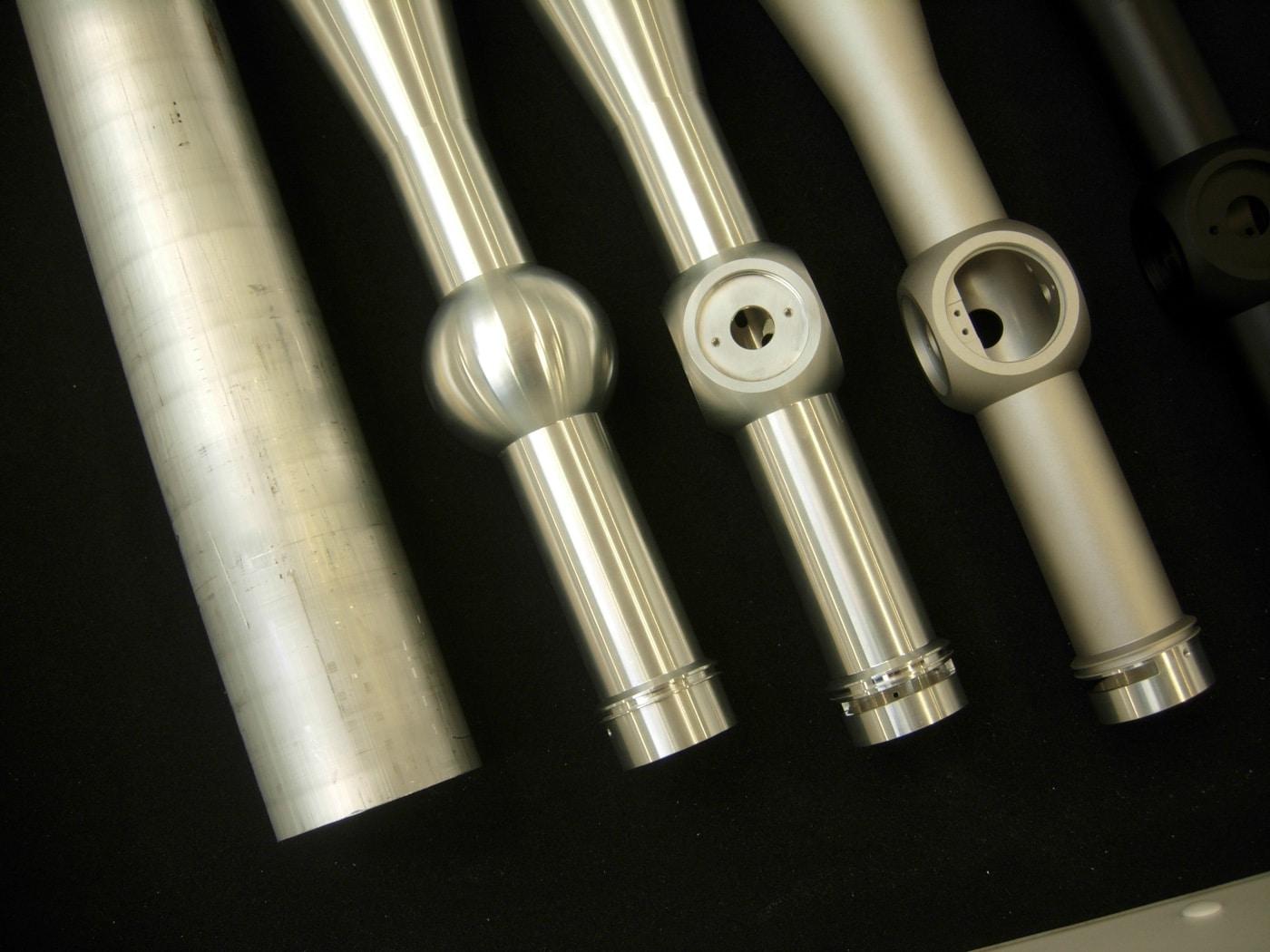

For rifle-scopes, FOV is specified as feet at 100 yards or meters at 100 meters. Contrary to popular myth, it has essentially nothing to do with the size of the objective lens or tube. These Leupold scopes illustrate:

FOV is a function of optical design, including ocular lens diameter.

The best balance of magnification, ER and FOV depends on a scope’s use. The Redfield 20X on my rimfire prone rifle has short ER, but recoil is almost nil. FOV is quite reasonable for the power, surely enough for deliberate bullseye shooting. The fixed-power and 1.5-5X variable scopes I like in big game cover have generous ERs and FOVs. Ditto the 4X and 2.5-8X and 3-9X variables that, to my mind, excel as all-around sights.

Going Big?

Rifle-scope magnification ranges have increased with a trend to bigger tubes. Stateside, Bill Weaver’s 3/4-inch scopes, then the 7/8-inch tubes of Noske and early-post-war Lyman and Leupold scopes, gave way to the 1-inch (25.4mm) measure of Weaver’s K4, introduced in 1947. European makers of that day — Hensoldt and Pecar, others — used 26mm tubes. By the time my “Gun Digest Book of Sporting Optics” was published in 2002, scope-makers on both sides of the Atlantic (Burris, Bushnell and Leupold; Kahles, Swarovski and Zeiss) had 30mm tubes. Schmidt & Bender listed a 34mm Police/Marksman II. Now 30mm tubes are supplanting 1-inch; 35- and 36-mm pipe have followed the 34mm. Swarovski’s dS has a 40mm tube.

Big tubes afford more assembly room for complex optical systems and lighted reticles. With standard-size lenses in erector assemblies, they also increase the range of W/E adjustment. Up-sizing glass inside enhances image quality.

Another result of bigger tubes: expanded magnification ranges. A 3-9×40 variable has a three-times range — top magnification three times the bottom. So has a 4-12X, a 6-18X. The 30mm tube loosed a herd of variables with four-times ranges. The 2.5-10X is shoving the 3-9X off-stage. Sales teams put engineers in hammerlocks to design five-, six-, even eight-times power ranges in 30mm scopes. The inevitable sequel: even bigger tubes. Schmidt & Bender’s P/M 3-27×56 and 5-45×56 have nine-times ranges! Zeiss gave its flagship Victory stable a 36mm 4.8-35×60 V8.

Scope weight affects utility. That V8 scales 34 ounces. Nightforce’s 5-25×56 comes in at 40, the Vortex Razor HD 4.5-27×56 at 48, both with 34mm pipe. These heavy optics shine for long-range shooting over bags or bipod, but they’re impractical for hunting. I try to hold scope weight within 15 percent of a hunting rifle’s weight. So, a 7-pound rifle gets, at most, a 17-ounce scope. Legions of trim, brilliant, low- and mid-range variables make this an easy rule to follow. Swarovski’s 3-9×36 Z3 and Leupold’s 2 .5-8×36 VX-2 hunker low and scale about 11.5 ounces.

Optical engineer Mark Thomas founded Kruger Optical in Sisters, Oregon after a decade at Leupold. He shares my reservations re: wide power ranges. “They add cost and complexity and require more components, including lenses to correct aberrations that appear as each lens works harder. The erector assembly must often be longer. Ditto the main tube. In sum, more numbers on the power dial mean more weight, higher cost.”

Leupold engineers echo his words. “Tolerances must be tighter for wide power ranges,” said one. “Figure plus or minus half a thousandth for erector cams. Lenses in a six-times scope travel about twice as far as in a three-times system, so variation in parts dimensions have twice the effect on the image. Maintaining sharp focus is hard at five- and six-times magnification; and vignetting increases at the low end.”

Shifting Perspectives

“You’ll like this scope,” said my pal Royal Stukey as he bellied onto a Wyoming bluff to target a rock with his rifle chambered for the 6.5 Creedmoor cartridge. It was 1,300 yards off. Indeed, his Nightforce 5.5-22×50 proved an ace! FOV was tiny at 22X, but firing over bags, we had time to seek out the football-size targets. That scope also showed mirage boiling from intervening draws. Its reticle, marked in minutes of angle (MOA) served for W/E adjustments he didn’t dial. A left-side turret dial brought the rocks into sharp focus and nixed parallax.

Parallax is easiest to describe as the visible shift it produces: the apparent movement of a target behind the reticle as you move your eye up and down or from side to side off the scope’s axis. Images formed by targets at different distances fall at different points along the scope’s axis. As the reticle doesn’t move along that axis, it meets a focused image only when the target is at a certain distance.

Parallax can’t be corrected with compound lenses. My old 20x Redfield takes it in hand with an adjustable objective (AO), a sleeve on the front bell. Rotated to a marked number representing the yardage, it ensures a crisp target image while “zeroing out” parallax. The AO is giving way to the more convenient turret dial.

Generally, the cost of a focus/parallax adjustment keeps it off low-power and entry-level scopes. Most scopes so deprived are built to be parallax-free at 100 or 150 yards. For rimfires, the magic distance is 75 yards. Whatever the range and whether or not there’s a focus/parallax dial, if your eye is centered behind the scope, you’ll get no parallax error.

Adjusting reticle focus matters too. It can bring big-scope optical clarity to a little scope! It’s done with the scope’s eyepiece, secured by a lock ring — or, increasingly, a rear (“fast focus”) ring that moves an internal assembly. Rotating either, you set the scope to sharpen your vision at the reticle, as an optometrist finds a lens prescription for your eyes. Don’t aim at an object for this task; your eye will try to sharpen that image. Rather, shut your eyes as you lift the empty rifle and point it at the empty northern sky. Open your eyes and rotate the eyepiece or ring until the reticle appears sharp. Repeat until the reticle is crisp at a glance. Snug the lock ring and forget it. Reticle focus is independent of target distance, and it won’t change until your eyes do.

Whatever the size or specifications of a rifle-scope, it’s useful only when adjusted to give you a practical zero and sharp images!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!