Ever wondered how rimfire ammo came to be? Here we walk through the history of its development.

There’s a cartoon floating around online called “The Invention of Archery.” Three guys are standing beside each other. The first guy says, I really wanna stab that guy, but he’s way over there.

Firearms were likely dreamt up along the same lines. Someone hit upon the idea that blackpowder stuffed down a tube, topped with a projectile, and touched off with fire, did spectacular damage downrange. Man, I want to knock that castle down, but it’s way over there.

In Europe, cannons showed up in Italy around 1320. For the next 200 years, firearms were essentially hand cannons—short, stout barrels loaded with blackpowder, then packed with rocks, pebbles, and sometimes arrows. You jabbed a hole in the barrel’s top or side with a smoldering stick or hot iron. Firing it was a two-person job. One soldier would hold the hand cannon (while presumably saying his prayers), and a second would grace the touch hole with the red poker. Anyone who’s seen a small wheel-mounted cannon go off—the type that shoots golf balls and is popular at sportsmen’s clubs in the country on chicken barbecue weekends—can imagine the thrill of holding such a device under one’s arm. Hand cannons weren’t particularly safe or accurate, but when they worked, look out.

By the 15th century, the matchlock came along. A lever, and later a trigger, was added under the barrel. When pulled, the “lock” dropped a lit cord or match into the flash pan and started the ignition process. There was a painful time delay between pulling the trigger, the lock dropping the match into a flash pan that ignited a sprinkle of powder, and the main charge in the barrel going off. Today, engineers still work to reduce that “lock time” between trigger pull and ignition, but now they’re shaving fractions of milliseconds. In contrast, a 1400s French arquebus could have taken several seconds to go off.

It’s worth noting, early firearms weren’t more accurate or deadlier than archery tackle, but they were faster to reload than a crossbow and less expensive and time-consuming to manufacture. Firearms flattened the training curve, too. An illiterate peasant with a matchlock and some instruction could knock a mounted knight off his horse in short order. Proficiency with lance or sword or bow could take years of training. Firearms democratized combat in the Middle Ages.

The matchlock evolved into the wheel lock, dog lock, and eventually the flintlock. Instead of a smoldering match dropped in the flash pan, a piece of flint struck steel sending a shower of sparks toward the blackpowder. Flintlocks didn’t require an always-smoldering length of cord, but they still had issues. The powder in the pan sent up a noxious yellow smoke cloud before the bullet took off that would often eclipse the target, affecting accuracy and spook game animals.

In 1800, British chemist Edward Charles Howard discovered fulminates—chemical compounds that exploded on impact. This discovery forever changed firearms for the better. A few years later, a Presbyterian minister in Scotland—annoyed that birds would flush as powder smoked in the pan of his flintlock—adopted fast-acting fulminates to his shotgun lock. British gunsmith Joseph Manton invented a cap-like system in 1814. Still, it took an American artist in Philadelphia, Joshua Shaw, to develop the sealed copper cup laden with fulminates, which we know today as the percussion cap.

Like the M1819 Hall Rifle and the British Brown Bess, many early percussion muskets were flintlock conversions. The flash pan was tossed, replaced with a metal “nipple” connected to the chamber’s powder by a small tube. Copper and sometimes brass percussion caps shaped like miniature top hats sat over the head of the exposed nipple. When you pulled the trigger, a heavy hammer dropped on the percussion cap, detonating the fulminates, which sent sparks to the powder in the barrel, and away the lead ball went.

An infantryman armed with a percussion musket or rifle would carry a pouch of caps and another of paper cartridges. To load, he’d rip open the powder end of the cartridge with his teeth, spill the premeasured slug of blackpowder down his musket barrel, seat the lead ball by hand, then use a ramrod to get the whole package snug at the bottom of the barrel. Musket shouldered, on went the percussion cap. After the first volley, it took a well-trained soldier 20 to 30 seconds to reload. A fighting regiment could get off three volleys a minute.

Throughout the 1800s, firearms development coincided with cartridge development. Engineers, inventors, gunsmiths, and crackpots tried various ways to speed reloads by integrating fulminate primer, powder and bullet into a single package—then they built guns around their idea.

In 1808, the Swiss gunsmith Jean Samuel Pauly developed a self-contained paper cartridge with primer snugged behind the bullet. You loaded this gun from the breech end, much like a modern break-action shotgun. When you pulled the trigger, a needle struck through the paper and detonated the primer. Frenchman Casimir Lefaucheux took this idea and replaced the paper for brass to develop the pinfire cartridge. Each round had a firing pin that jutted off the cartridge’s side at a 90-degree angle. Trip the trigger on an early pinfire, and the hammer dropped, striking the integrated pin, detonating the primer. Then, around 1845, another Frenchman, Louis-Nicolas Flobert, created the first modern firearm cartridge.

The Parisian Flobert took a simple copper cup, loaded it with fulminate primer compound and topped it with a round ball—essentially a bullet crimped to a percussion cap. There was no real rim or flange at a 90-degree angle in his first designs. The case head had a taper that wedged the cartridge in the chamber. There was no powder in the case, only the primer and the lead ball. Flobert’s rifles and revolvers were designed for indoor parlor shooting or whacking a troublesome rodent in the pantry. They were gallery guns, designed to punch paper or tip over little tin animals at a few steps, much like gallery shooting games prevalent at American carnivals and country fairs until recent times. The early Flobert designs had heavy hammers that crushed the primer side of the self-contained metallic cartridge. In later versions, he added a firing pin to the action.

At the London Exposition of 1851, Flobert exhibited his small .22-caliber rifle. Attending were two Americans, Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson. They were impressed, and by 1857 they had developed a new cartridge of similar design, the .22 Short, for the new Smith & Wesson Model 1 revolver. They patented the cartridge on April 17, 1860, as the “S&W .22 Rim Fire.”

This new metallic cartridge had a straight case and hollow rim—a first in the United States. The hollow rim allowed Smith & Wesson to use a wet priming mixture, spun to the rim’s edge and dried. You could then add the powder to the case without mixing it with powdered primer—a problem that led to constant misfires in the duo’s other post-London designs. Smith & Wesson loaded its first .22s with 4 grains of fine blackpowder. The powder sat atop a perforated-paper wad to further prevent the dried primer from mixing with the powder. (Later, as S&W perfected the wet-primer process, it dropped the paper disc.) The head of the case was convex or dished out, not flat like modern rimfire ammo. There was no headstamp. Smith & Wesson thought the dished head helped more evenly distribute the primer around the rim. Pull the trigger and a firing pin stabbed the brass case’s rim, igniting the primer.

Like today, yesteryear’s ammo makers loaded the first .22 Shorts with a 29-grain lead round-nose bullet. The bullet had a tapered heel that reduced the backside of its diameter so it would fit in the case. This design became known as a “heeled” or “outside lubricated” design. You applied wax or grease to the bullet outside the case to prevent lead buildup in the bore. (All .22 rimfire bullets are still heeled and outside lubricated except for the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire.)

Smith & Wesson’s 1860 patent shows three lubrication grooves, or cannelure, along the bullet’s diameter. The cartridge case had a light crimp on the bottommost cannelure to secure the bullet in place. With this design, the diameter of the brass case matched the outside caliber diameter of the bullet. The bullet base was convex or dished as if you pressed a BB into the lead—a likely design holdover from the caseless Volcanic and Rocket Ball cartridges that were cutting edge in their day. Modern bullet and cartridge designs have abandoned most of these principles, but you could never call these features unsuccessful. The .22 rimfires are still the most widely produced arms and ammo in the world. The antique .22 Short remained an Olympian as the official round for international rapid-fire pistol competition until 2004, when the .22 LR replaced it.

While underpowered by today’s standards, the Model 1 in .22 Short became a popular compact self-defense revolver with soldiers on both sides of the Civil War. Smith & Wesson’s first pistol and cartridge were a major early financial success, too, thanks mainly to the rimfire manufacturing process it developed. Like copper and copper-alloys like brass, soft metal could be rolled into thin sheet metal, then punched into small discs. These discs were then “drawn” into little tubes with one end closed. A rim was “bumped” into the head, much like how a handloader uses a resizing die to shape centerfire brass. The malleable metal didn’t tear or split through the forming process. Hundreds of these little cups could be drawn and bumped in a single pass of a 19th-century machine press. This process made ammunition for the Model 1 widely available and affordable. Several U.S. manufacturers started producing the easy-to-make “.22 Rim Fire.” Overseas, Eley of England manufactured it as the .230 Rimfire. By 1871, annual round production hit 30 million.

Flobert’s cartridge developed more of a rim and became known as the .22 BB Cap. The BB stands for “bullet breech,” a reference to the breech-end loading in Flobert rifles and pistols. (Later came the .22 CB for Conical Bullet.) When multiple variations on the Smith & Wesson cartridge appeared in the 1870s, including the .22 Long in 1871, the firm renamed it the .22 Short.

The hollow rim and wet-priming process pioneered by Smith & Wesson did several things very well. First, the rim of a rimfire held the cartridge securely in the breechface. A closed action effectively clamped the round in place. (Many of the early Flobert actions didn’t even lock. A stout mainspring held tight enough.)

Second, the ammunition was relatively weather-sealed with the bullet pressed in place surrounded by a copper case—a dramatic improvement over loose powder and paper cartridges.

Third, the malleable copper case created a seal at the breech end and further expanded to the chamber on detonation, so all the toxic fulminate gases and blackpowder smoke went down the barrel and away from the shooter’s face.

Four, the rim provided an excellent gripping surface for reliable extraction and ejection. (Extraction and ejection issues plagued early needle-fires and pinfires).

Five, the rim provided an effective way to measure and build proper headspace into bolts and barrels, which helped make the round accurate. Headspace is the distance between the bolt face and the chamber’s part that prevents the case from moving forward. With a rimfire, the headspace takes up the rim thickness, sandwiched between the bolt face and the breech.

Inventors flooded patent offices in the U.S. and Europe with rimfire designs between the 1860s and 1890s. There were many new but inconsequential .22s developed, but most were much larger.

In 1860, B. Tyler Henry patented a rimfire repeater with a cartridge called the .44 Henry Flat. By 1865, repeating carbines utilizing .56- and .58-caliber rimfire cartridges like the Sharps and the Spencer outmatched all muzzleloading small arms on the battlefield and helped the North win the Civil War. The U.S. Army reportedly resisted the Spencer rifle, chambered in .56-56 Spencer, but after President Abraham Lincoln shot a Spencer himself in 1863, he insisted a large order get placed. After the war, the Winchester 1866 “yellow boy” in .44 Rimfire went on to win the West—and Winchester the imaginations of shooters everywhere. By 1880, a catalog for Union Metallic Cartridge Company listed 40 rimfire cartridges for sale. Only two were .22s. More than half ranged between the Colt .41 and .58 Joslyn.

Rimmed big-bore cartridges dominated small arms until the advent of smokeless powder required cartridges to handle high pressures. Like the French Poudre B, early smokeless powders proved three times more potent than blackpowder by weight and produced much less smoke. Rimfire cases by design straddled the pressure curve from the very beginning. The brass case had to be soft enough for a firing pin to depress the rim and ignite the primer and strong enough not to blow out the case head or split the case in the chamber.

In small doses, smokeless worked well in rimfire cartridges, but the brass of big bores like the .44 Henry pushed a 200-grain bullet with 28 grains of blackpowder and could not handle the equivalent weight of smokeless or semi-smokeless. One of the largest rimfires ever developed, the .58 Miller, sent a 500-grain bullet downrange pushed by 60 grains of blackpowder. The smokeless powder had much different pressure demands and quickly ushered the development of centerfire priming and beefed-up case heads.

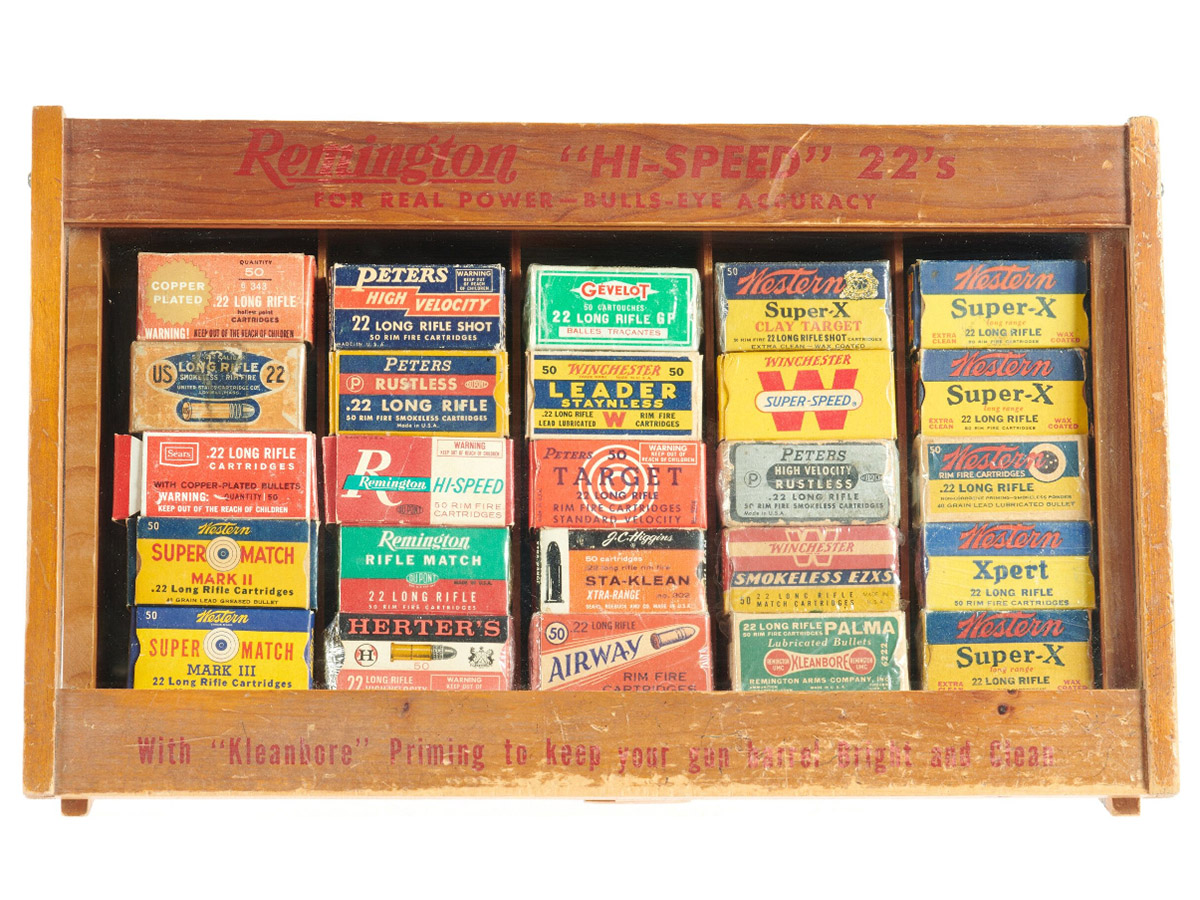

Around 1887, .22 Shorts hit the market loaded with semi-smokeless and smokeless powder. This development brought together all the features of modern rimfire ammunition into a single package—all of which persist today. The brass case had a hollow rim spun full of wet primer. The heeled, outside-lubricated lead bullet matched the diameter of the case. Makers loaded the self-contained little rimfire cartridge with smokeless powder. Many iterations of these features would come and go, but none would take over like the world-famous .22 Long Rifle—by far the most widely produced small arms cartridge the world has ever seen.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt from Rimfire Revolution: A Complete Guide to Modern .22 Rifles.

More On Rimfire Ammo