Even positive changes can be hard to accept. Long before the M1 Garand rifle was in widespread service in the US military, it had its share of detractors. A number of these objectors simply disagreed with the Army’s decision to adopt a semi-automatic rifle at all. They argued that the M1903 Springfield bolt-action rifle was more than capable as a battle rifle, that new semi-automatic designs were unproven, potentially too fragile or complex, and that troops would waste ammunition.

At the time, these old-school concerns were certainly given some credence, but the Army had carefully considered these issues well before adopting the M1 in 1936. John Garand, the man who made the M1 Garand, had developed a rifle that served as America’s primary battle rifle until 1958.

A more significant and modern challenge to the M1 rifle arose with the Johnson semi-automatic rifle, which first appeared in 1938. Melvin M. Johnson was a Marine Corps Reserve officer and prospective gun designer. He had several concerns about the M1 Garand’s design, and independently, Johnson assembled a rifle that became a widely discussed competitor to the M1 rifle, even in the United States Senate.

M1941 Rifle: “Betsy” Is Born

Johnson nicknamed the firearms he designed, and he dubbed his first creation, the Johnson rifle, as “Betsy”. He would later name his M1941 Johnson machine gun as “Emma.” To put the Johnson rifle into context, I used Melvin Johnson’s own description, coming from his 1945 book “Automatic Weapons of the World” (published by William Morrow and Company):

“The Johnson is a short-recoil-operated, 10-shot, rotary-magazine-fed, semiautomatic rifle, having an air-cooled removable barrel and an 8-lug turning bolt locking on 20 degrees rotation. The magazine can be loaded by standard rifle clips (chargers) or single rounds, with the bolt closed or open, an uncommon feature in modern small arms, permitting the operator to keep the magazine entirely full at all times without opening the bolt or disturbing the round in the chamber. Thus, a total of 11 rounds can be carried in this weapon. The magazine is emptied by depressing the hinged loading cover.

Upon firing, the barrel and bolt recoil about 3/16th of an inch when the bolt unlocking cam hits a cam face in the receiver. This causes the bolt to rotate suddenly 20 degrees, disengaging the 8 lugs from corresponding abutments in the barrel collar. The total barrel recoil is about 3/8th of an inch. As the bolt rotates, the locking cam and firing pin assembly is cammed backward. The bolt assembly continues rearward under momentum aided by residual pressure. The receiver being closed on top to keep out rain and dirt, the empty case is ejected to the side. The barrel return spring and latch assembly functions to return the barrel to battery after unlocking. This latch is quickly disengaged with a bullet point to remove the barrel for cleaning or replacement.

The receiver’s peep sight is elevated by a sliding ramp in hundred-yard increments; windage is adjusted in half-minute clicks. The complete rifle weighs 9.5 pounds and its overall length is 45 inches. Two bayonets were developed for this weapon. One is an 8-inch blade, dagger type, mounted on the barrel. The other is a sword type with 16-inch blade, mounted on the fore end so as not to recoil with the barrel in firing. Both types were available in 1940. The Netherlands adopted the dagger type. Although capable of functioning with standard 7 mm ammunition and U.S. .30 M2 (150-grain bullet), the Johnson was primarily designed for the U.S. .30 M1 ammunition with 172-grain boat-tail bullet.”

The Magazine Conundrum

Much of the debate over the relative merits of the Johnson rifle compared to the M1 Garand centered on the magazine, and this was ultimately the Johnson’s greatest perceived advantage. The Johnson 10-round rotary magazine could be loaded using standard 5-round stripper clips for the M1903 rifle, or with individual rounds. The ability to “top off” the Johnson magazine was a highly touted feature.

Even today, there are those who deride the M1 rifle’s internal magazine and its eight-round “en-bloc” clip. Granted, it is a unique design, but John Garand’s system met all the Ordnance Department’s early 1930s requirements for the first semi-auto rifle — particularly their disapproval of any sort of detachable box magazine.

The Johnson’s rotary magazine offered at least two more rounds than the Garand, and the ability to use existing 5-round stripper clips was an early advantage. But at this time, few could calculate the tremendous firepower provided by a squad of experienced American infantrymen equipped with M1 rifles.

The Garand Ping

When the M1 rifle fires the eighth round of its internal magazine, the thin metal en-bloc clip is ejected from the weapon. The metallic ping of the ammunition clasp striking the receiver is a distinctive characteristic of the rifle. That audio signature is easily heard by the shooter — particularly in the structured environment of a shooting range.

Unfortunately, the “Garand ping” made an impression on many American troops, and even before the war, this led to some wild imaginations that the peculiar sound would give away the G.I.’s position and betray that his rifle was empty. This combat myth was even discussed in the US Senate, and although debunked by fact and common sense, the battlefield in a firefight is an extremely noisy place, and the M1 rifle could be swiftly reloaded by most troops. Even so, the old wives’ tale lives on today, and you’ll overhear its retelling at gun shows or see it posted online. Through WWII and the Korean War, there were no verified cases of a US soldier or Marine becoming a casualty due to the sound of an ejecting M1 en-bloc clip.

Speed-loading and reloading comparisons between the M1 Garand and the Johnson rifle ultimately came down to user preference and training. With more than four million M1 rifles made through 1945, we can safely conclude that while the eight-round internal magazine is unique, it was also highly effective.

The Garand rifle could also accept the standard rifle bayonet, while the Johnson could not. Johnson was dismissive of bayonets in general but eventually created a spike bayonet to meet the requirement. It seems that the Army couldn’t get past Johnson’s attitude and poor timing, and his 10-round rotary magazine was never enough to seriously challenge the M1’s position as America’s standard rifle.

A US Senate Committee Hearing

The merits of the Johnson rifle were discussed in the US Senate during a Committee on Military Affairs meeting on May 29, 1940. At that date, the German Army was rampaging across northern France, and the British Expeditionary Force was being evacuated at Dunkirk. Military analysts around the world were shocked by the German Blitzkrieg, and in America, it was apparent that the US military was not ready for the war that was soon to come.

In the transcript of that hearing, I found that Brigadier General Walter A. Delamater, the President of the National Guard Association, offered a sobering assessment. General Delamater realized that the US military had several capable rifle designs, including two semiautomatic rifles — when almost every other armed force in the world had none. Even so, he reminded the Senators that the key factor would be the speed and efficiency of American manufacturing:

“I think that we all feel today, in view of world conditions, that it is necessary that something should be done. I don’t think we have time to fuss around and delay. I don’t think we have time to quibble over some little preferences — whether this is a little better or that is a little better. I think the main thing is our equipment. How long is it going to take us to get equipped; time is the most important factor…I think it is recognized that we’ve got to have more firepower.

If we went into service today, we would have three rifles — we would have the Garand, and the Springfield, and the Enfield — all .30 caliber. The Johnson rifle can utilize Springfield barrels, as has been testified to here today; it can also use the Springfield clip. We can have the guns come along in volume production as an automatic or semiautomatic weapon, and for that reason, I think the Army can use them. I agree that the ideal situation is to have one rifle, but I don’t think we are at the point where we have an ideal situation. The ideal situation would be not to have any war. But, nevertheless, we may be facing that. To my mind it is more important to have two semiautomatic rifles than to have very few of one. I think the thing to determine is the manufacturability of this weapon, and how fast the Garands can be turned out. We also realize you are now planning to increase the number of men in service, and if something does happen, we know we have to add still more men and many more semiautomatic rifles.”

More than anything else, manufacturing would be the greatest hurdle that the Johnson rifle (and light machine gun) faced. The M1 Garand had already been revised and by mid-1940 the M1 rifle was ramping up production. Maynard Johnson had his fans and supporters, but what he did not have was a factory — and that would soon become a significant problem. All the primary US firearms manufacturers were occupied, and Johnson would have to scramble to find production facilities.

Netherlands Purchasing Commission

By mid-July 1940, Johnson traveled to New York to present a second demonstration of his rifle (and light machine gun) to officers of the recently established Netherlands Purchasing Commission, established to secure modern war materiel for the forces of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). With a force of about 85,000 men, the KNIL sought to modernize its equipment quickly to defend against the increasingly aggressive Japanese Empire.

In mid-July 1940, Maynard Johnson was called to New York to give another demonstration of his semiautomatic rifle to representatives of the Dutch army and navy from the newly formed Netherlands Purchasing Commission (NPC). The NFC was a joint committee of the Navy and the Colonial Army established to purchase war materiel.

The Dutch government in exile (in England) had paid close attention to the Senate hearings concerning the Johnson rifle. The Dutch were impressed by Johnson’s design and were ready to purchase. By August 1940, the Netherlands Purchasing Commission placed an initial order for 10,200 Johnson rifles and 500 light machine guns with an estimated price of $125 per rifle and $260 per LMG. Including spare parts and accessories, the contract totaled nearly $2 million. While the finances were attractive, the Dutch made it clear that Johnson was responsible for the production and quality control of the firearms.

Ultimately, Johnson reached an agreement with Universal Windings to produce most of the metal components for his rifle and LMG, and Cranston Arms was established as a subsidiary of Universal Windings to handle the work. Sights were provided by the Lyman Gun Sight Company, while The American Paper Tube Company made the stocks. The barrels were the final hurdle, and as Johnson could not find a firearms manufacturer to handle the job, the Johnson Automatics Manufacturing Company (JAMCO) was formed.

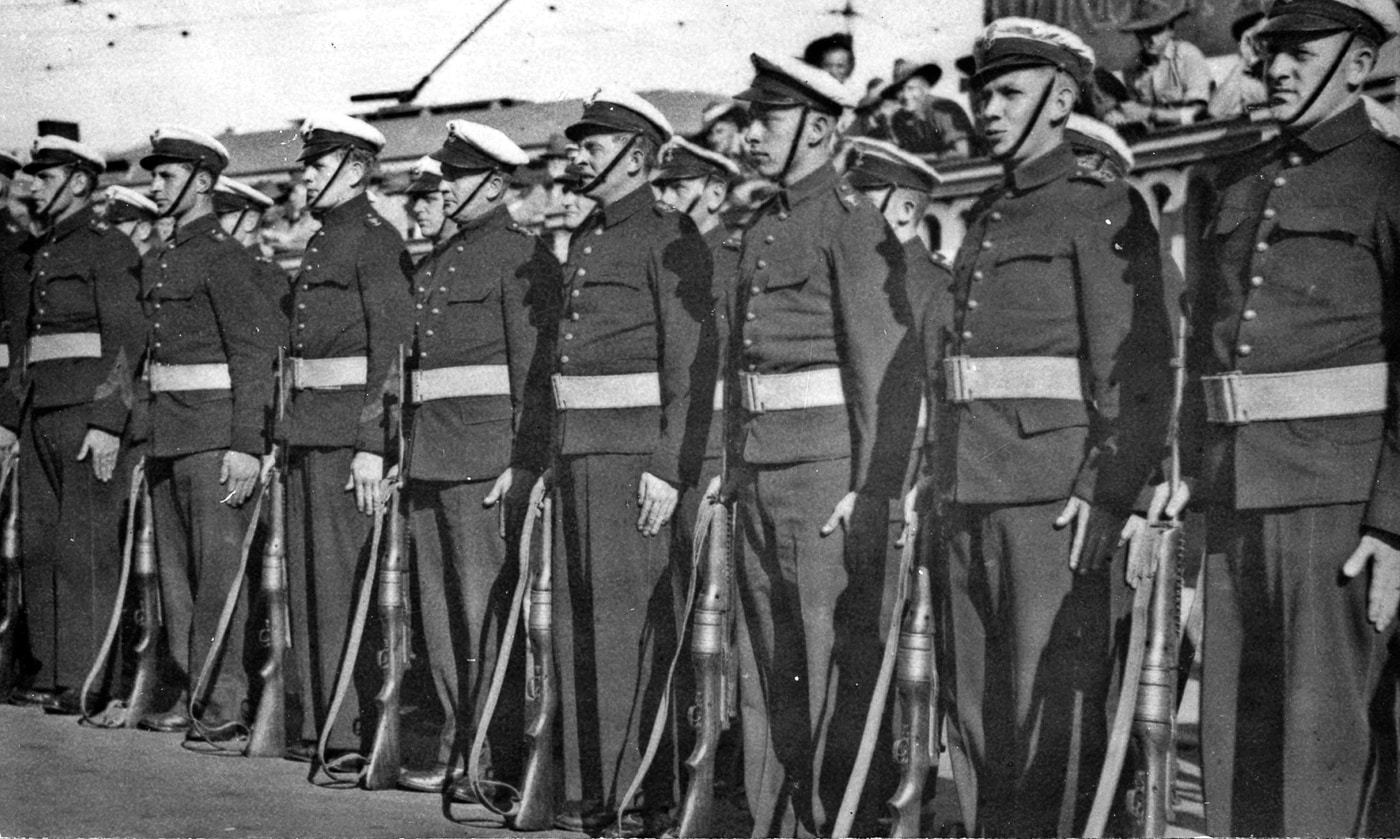

The Johnson rifle picked up the Dutch designation of “M1941”, and although nearly 22,000 were manufactured, only about 3,000 M1941 rifles made it to Dutch KNIL forces before Japanese troops took over the East Indies on March 8, 1942. Very few photographs of the M1941 rifle are available, and most are from Dutch sources. Since the East Indies had fallen while the bulk of the new rifles were still in transit, most images show the M1941 in the hands of Dutch sailors or marines on parade or in training in Australia. The rifles soldiered on after WWII, remaining in service with the Dutch marines and other special operations groups. Some of the Dutch rifles were sold on the surplus market in the late 1950s.

There is some anecdotal evidence that the M1941 rifles were provided to the Nationalist Chinese during World War II, and a handful of Johnson rifles made their way into the hands of Chinese communist troops during the Korean War. The M1941 even played a small role in the attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro in the 1961 Bay of Pigs operation.

Tell It to the Marines

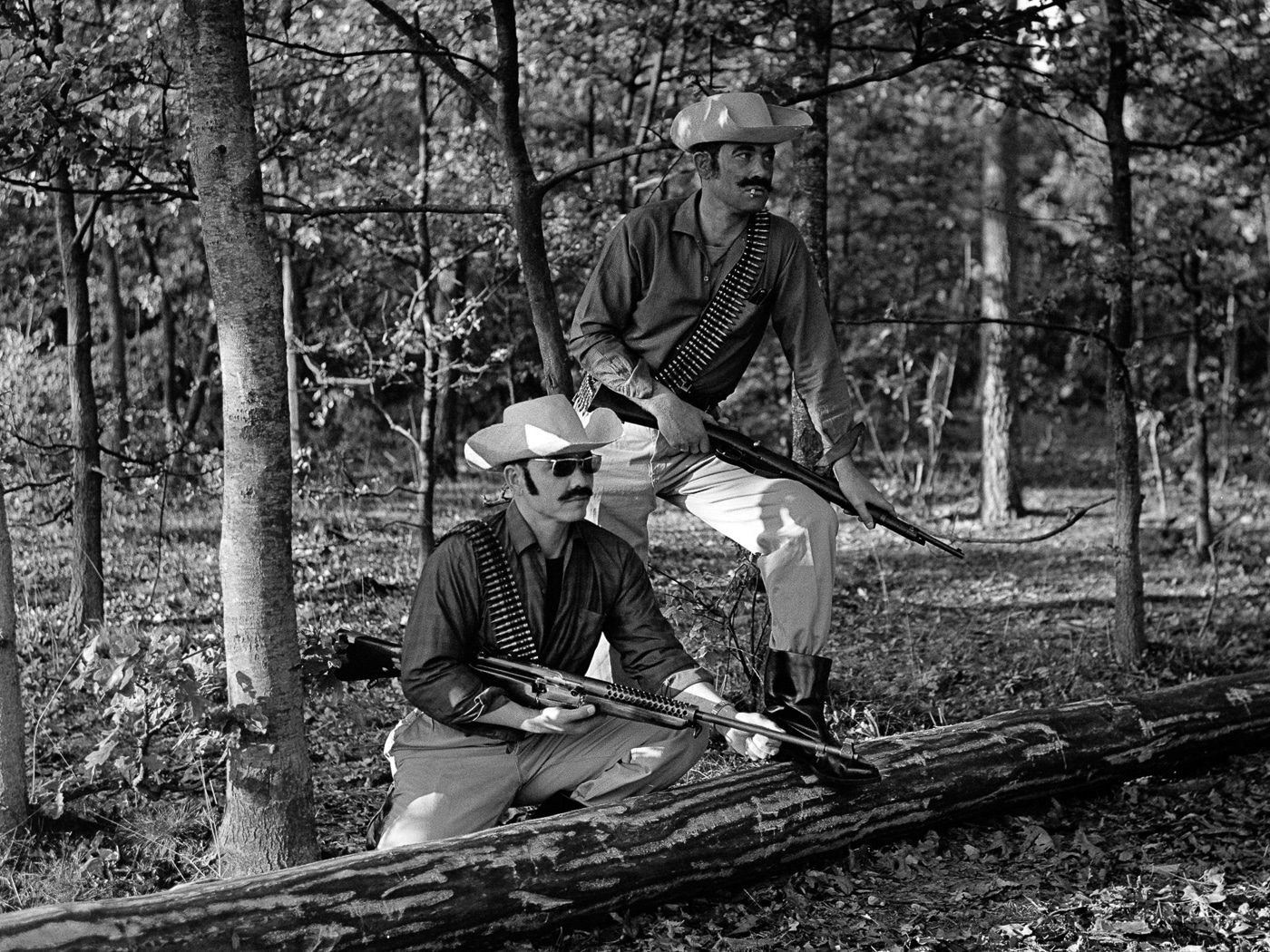

As the USMC 1st Parachute Battalion was readied for combat in the Solomon Islands, the “Paramarines” had a wide range of small arms in their possession. In addition to more than 500 Reising .45-caliber Model 55 folding-stock SMGs, the airborne Leathernecks had 87 Johnson Light Machine guns (purchased from the embargoed Dutch inventory) and 23 M1941 Johnson rifles donated by Melvin Johnson.

Thus began the small-in-number but big-in-legend career of Johnson firearms in USMC service. Part of the attraction of the Johnson LMG and rifle for the Marine paratroops came from the fact that the barrels could be easily removed for airborne operations. But the Marines never parachuted into combat in WWII, and the Johnson rifles were used by scout/sniper teams during the Solomon Islands campaign.

In the inevitable comparisons to the M1 Garand rifle, the M1941 Johnson performed equally well in combat. After the fighting on Bougainville, Lieutenant Colonel Victor Krulak of the 1st Parachute Regiment reported: “The Johnson Rifle, caliber .30 performed similarly with the M1 rifle. Found little difference between the two.”

During 1943, the Johnson rifle found itself in quiet competition with another “M1”, in this case, it was the M1A1, the folding-stock version of the M1 Carbine. The Marine paratroopers were still expecting to perform combat jumps, and the M1A1 Carbine was greatly desired, but its availability was uncertain. The Johnson rifle was considered a strong substitute, but the M1941 was no longer in production, and for the cash-strapped Marine Corps, the cost of a Johnson rifle (about $135 each) dwarfed the price of a M1 Carbine (approximately $45 each).

Despite glowing reports from individual Marines, the M1941 Johnson rifle had become an unnecessary logistical burden. The debate was ended as the USMC Commandant commented to the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance: “The performance of the Johnson semi-automatic rifle is equivalent to that of the M1. It does not have sufficient advantage over the M1 to warrant its continued procurement.”

Fitting into the USMC TO&E

I was able to find some description of how the Johnson rifle fit into the USMC Tables of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) via the Marine Corps publication “Silk Chutes and Hard Fighting: U.S. Marine Corps Parachute Units in World War II” by Lieutenant Colonel Jon T. Hoffman, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve (History and Museums Division HQ, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C. 1999)

The first official parachute table of organization, issued in March of 1941, authorized a battalion of three “line companies” and a headquarters unit. The line companies consisted of a weapons platoon (three 60mm mortars and three light machine guns) and three rifle platoons of three 10-man squads armed with six rifles, two Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs), and two Thompson submachine guns. The standard squad for regular infantry at the time was nine men, with eight rifles and a single BAR.

A 1942 revision to the tables did away with the weapons platoons, distributing one 60mm mortar to each rifle platoon and getting rid of the machine guns. The latter change was not as drastic as it might appear, since each rifle squad was to have three Johnson light machine guns. The remaining “rifle men” were supposed to carry Reising submachine guns. This mix of automatic weapons theoretically gave the parachute squad an immense amount of firepower. As things turned out, the Johnson took a long time to get to the forces in the field and the Reising proved to be an unreliable weapon.

The battalion also benefitted from its additional time in the States, as it received Johnson rifles and light machine guns in place of the reviled Reisings.

The 1943 tables created a regimental structure consisting of a headquarters company and a weapons company. The latter unit of seven officers and 172 men served as a pool of extra firepower for the lightly armed battalions. The company was supposed to field four 81mm mortars, one dozen each of the air-cooled and water-cooled .30-caliber machine guns, two .50-caliber machine guns, two bazookas, and eight grenade launchers. Headquarters also authorized a change in the size of the battalions from 24 officers and 508 enlisted Marines to 23 officers and 568 enlisted. The additional personnel were all in the headquarters company, though 33 of them formed a demolitions platoon that did add directly to the battalion’s combat power.

Beyond that, I MAC allowed the line companies to reestablish weapons platoons exactly like those deleted in 1942. That move increased the authorized strength of each battalion by another three officers and 87 enlisted men (though manpower for these units was often taken out of hide). The new rifle squad of 11 men was supposed to have three Johnson machine guns, three Johnson rifles, and five Reisings, but by this time the parachute regiment informally had adopted the fire team concept of three three-man teams and a squad leader.

M1 vs. M1941 in the Final Analysis

Looking back at the Garand versus Johnson rifle debate, the question was never really about the basic concept of semi-automatic rifle design or whether such rifles were appropriate for American troops; rather, it concerned the nuances of how that new technology was applied.

Indeed, the US military was already blessed with one of the finest bolt-action rifles of all time — the M1903 Springfield. Even if the M1 Garand or the M1941 Johnson had never been available, American infantrymen would have had a war-winning battle rifle in their hands, a weapon already proven in World War I. However, the M1 Garand gave US infantry units a level of firepower never seen on the battlefield.

While most WWII combatants only flirted with semi-auto rifle designs during the conflict, America had two fine self-loading rifles to choose from, even before entering combat. While the Johnson rifle is now a minor footnote in the history of U.S. military firearms, it serves as an important reminder that we can always improve and that we never stop working to enhance the capabilities of our fighting forces.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!