Are Competition Triggers For Self-Defense A Good Idea?

When it comes to the guns you use to defend yourself, is it smart to modify them with competition triggers?

Before we get to making mockery of those who insist on “the best trigger possible” in a firearm to be used for defense, we need to lay out the parameters of just what it is we’re talking about.

In truth, most triggers are good enough. Most, even those that are deemed “beyond hope” by the cognoscenti will actually do the job when required. But “good enough” is a small comfort. And this is, after all, America … where we have choices.

You just want to be careful what you choose.

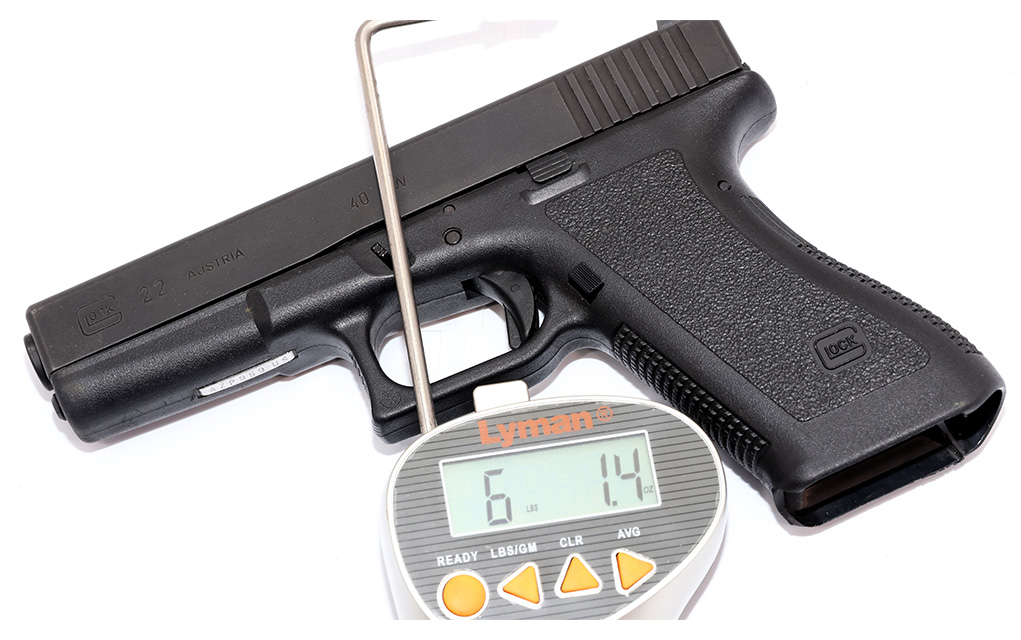

You will search for a long time to find someone more dismissive of the Glock trigger than myself. Not to pick on them in particular (oh heck, why not?), but a spongy, gritty, 6-pounds-plus trigger isn’t ideal for good marksmanship. And that’s the best, out-of-the-box trigger that they tout. Some places, like the NYPD, had even crappier triggers foisted upon them. (If you’ve never tested the trigger pull of an NYPD 1 or NYPD 2, consider yourself lucky.) The temptation to improve such a trigger pull can be great, and in a lot of instances it can be a good thing.

But, like so much in life, it’s easy to go too far.

Two examples come to mind: pro shooters on the USPSA/IPSC circuit and law enforcement. People will read about, or hear about, the top shooters using trigger pulls in the 2 pounds or less region.

“Oh, that’s what it takes to shoot fast? Then, sign me up for some of that.”

Actually, no. If you want to shoot fast, you can manage very quick shooting while using a regular trigger pull in the 3½-pound level, or even a 4-pound trigger. As long as it’s clean and crisp, you’ll be able to shoot as quickly as you need to in a defensive situation. So why do the Grandmasters use such light triggers? Because they’re trying to beat other Grandmasters, that’s why. (I know it sounds obvious, but there it is.)

The Real World Application

If you find yourself in need of shooting in a defensive situation, you have to use both good marksmanship and good tactical awareness. It’s entirely possible to shoot too quickly in a defensive situation. The tactical awareness needed in a match consists solely of, “Is the target the correct color? Have I engaged it already?”

For a defensive situation, you’re not going to need “splits” at the 0.15-second level, which is the working space of the GMs you read about. It’s more like a half-second, and you don’t need a 2-pound trigger for that.

So, what if you do have a trigger that light on your sidearm? Well, the chances of stress, cold weather, gloves, or just being jostled while handling your sidearm greatly increase the chances of an accidental or unintentional discharge. Simply holstering can be problematic, if something like a jacket hem or a drawstring gets in the path of the trigger as you are finishing the shove home.

The old adage that “every bullet has a lawyer attached” is one you have to keep in mind. On the range, an accidental discharge/unintended discharge (AD/UD) will get you DQ’d from a match. It might even be cause for your gun club membership to be looked into. Out in public, an AD/UD could be a lot more serious. You will have your CPL looked at. You might find civil action being brought, from the damage your bullet created or even the emotional harm experienced by bystanders.

Back in the old days, when it was mostly (or only) law enforcement officers who were packing, an AD/UD was cause for their embarrassment and not much else. The department might or might not have taken some disciplinary action, but that was it. These days, even LE gets put on notice for an accidental or unintended discharge.

And the rest of us? It could be bad.

The Other Side Of The Coin

But shouldn’t a bad trigger pull be improved if it can be? You bet. There are rational arguments to be made for a better trigger pull, such as improving accuracy and allowing for better decision-making.

I’m not saying that improving your trigger pull is always a bad thing. Just keep it reasonable. Taking a really ugly 6-plus-pound trigger pull and bringing it down to a clean four will seem like a huge improvement. And it is.

Now, if you want to make the legal side of this a better proposition for you, engage in a bit of planning. Peruse the manufacturer’s spec sheets for a pistol similar to yours. (So, you have a Glock, that means pretty much any maker of a striker-fired pistol then.) Find a competitor’s spec sheet that lists their pistol as having a 4-pound trigger pull. Now take your Glock and an aftermarket trigger to a pistolsmith and work the details out. You want it in writing that the task was to “match the other maker’s trigger pull.” (You could just trade guns over the counter at the gun store and get that 4-pound pull, but that would be too easy.)

If you then use that pistol in a defensive situation, and the question comes up as to the trigger pull, you’re now on record as simply matching the factory-spec trigger pull of the competitor’s model—nothing untoward about that. Of course, the pistolsmith will have to be onboard with this, no fair blindsiding them when the question comes up.

Law Enforcement Is Different

The law enforcement aspect mentioned isn’t so much an LE departmental thing as it is LE equipment. The problem here is one of trigger disparity. In Patrol Rifle classes, we’d run into officers who were issued Glocks with unaltered factory triggers (as required by, or issued by, the department), but the officers, when they were authorized to do so, had purchased an AR-15 for duty work. (And good on them for having done so.)

In many instances, that AR-15 came with a match trigger. They now had two firearm tools at their disposal, one with a 3-pound trigger and the other with a 6-pound trigger. Despite giving them a heads-up, there would be unintentional discharges from the trigger-pull disparity. Why?

Having spent years up to that point training with Glocks (a lot of departments were late in allowing/issuing AR-15s), the officers had fired many qualification courses with the long and heavy factory pistol trigger. Then, arriving for the Patrol Rifle class, they’d have a short-travel trigger with maybe as much as 3.5 pounds of pressure required. So, when firing their AR-15, just about the time they would have taken up most of the slack and trigger weight on their Glocks, their AR-15 would discharge.

Often, this was near the target, but not at the point they planned on striking. Sometimes it was on the range floor, into the dirt or gravel below the target frame. It wasn’t easy learning to switch from one to the other. Transition drills were almost a comedy of errors. Officers who had now become accustomed to the AR trigger when switching to their Glock, short-pressed the Glock trigger, subconsciously expecting it to go off at 3.5 pounds. (Nope, it’s never going to do that.)

Had they just opted for the mil-spec trigger pull on an AR-15, they would have been all set. The USGI specs for an M16/M4 are close enough to the actual specs on a Glock that the two are in sync when box-stock. It’s when they changed one of them that created the disparity.

The Value Of Uniformity

I’ll admit, the temptation to improve is great. And, in some instances, it’s never been easier. It used to be difficult to improve the AR-15: Now you have no lack of “packet” triggers you can just drop in, delivering whatever trigger pull you desire. The 1911 can now gain that with the Nighthawk drop-in trigger pack. But Nighthawk knows how to build a pistol for defense, and the trigger weight it provides? About 3¾ to 4 pounds. Sound familiar? An online search for improved Glock triggers will produce a tsunami of pages. So, keep your trigger pull weight search within proper limits.

And if you’re going to depend on an array of firearms for defense, it would be a good idea to have them all with trigger pulls in a reasonable closeness to each other in pull length and weight. Here, I can point to myself as either a bad example, or an exemplar, depending on how you want to approach it. For a long time, I carried a 1911 with a match-grade (well, match-grade back in the 1980s) trigger pull of just under 4 pounds. My backup? One or another double-action revolver. They represent a combo more disparate than the Glock/AR-15 example I just gave.

However, I was shooting three, four, or five times a week in different types of competition, and used both 1911s and revolvers in those competitions. You’ve heard of the theory that it takes 10,000 hours of some kind of activity or practice in order to excel at it? I’m not going to say I’m some kind of genius or grandmaster shooter, but I passed the 10,000 of activity level back before Bill Clinton got in trouble with his intern.

But it took a lot of work, and that’s not something a whole lot of people have the time for or the willingness to invest in.

What To Do, Then?

Simple: If the trigger pull on the pistol you have selected for defense is truly atrocious, you have two choices—change to something with a better trigger or have your trigger pull improved. But don’t seek to make your trigger pull like that of the pro shooters, the sponsored shooters who you might read about in match results. They work hard to get accustomed to those light triggers and use them for match work.

And if you’re going to depend on a battery of firearms, then you’ve got some planning ahead of you. Figure out the one with the worst trigger. See how much it can be improved, and if it can be brought into the “reasonable” region. Then, have the rest of them tuned to match the one that was the worst, so ideally they all match. If they can’t be made to match, then keep those trigger pulls reasonably close, and life will be good. At least as far as managing triggers is concerned.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the June 2025 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More Knowledge For The Armed Citizen: